The Crystal Palace. 10-11 Wood Street.

An illustrated look back at its Past

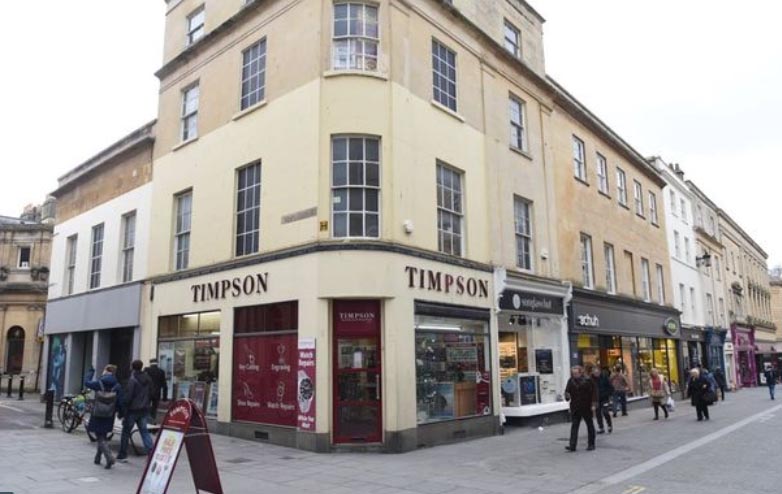

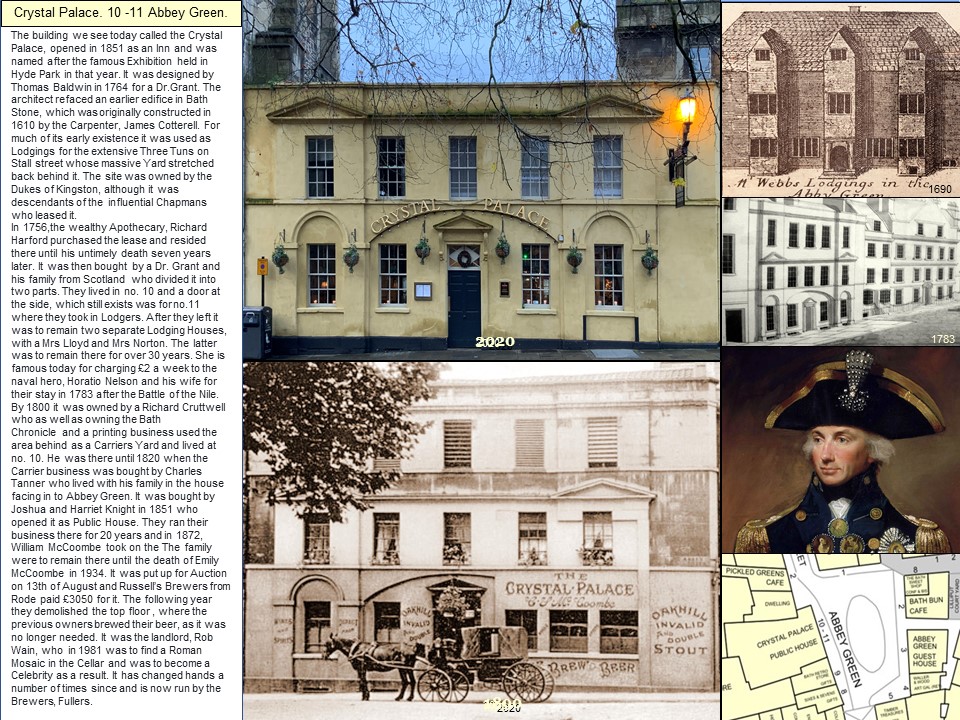

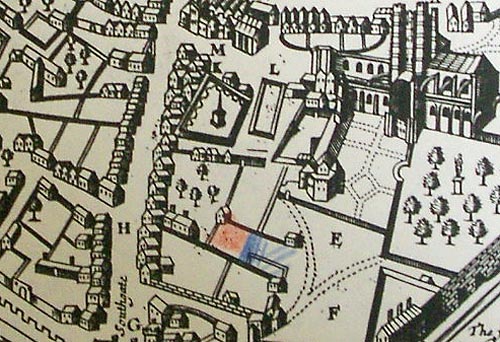

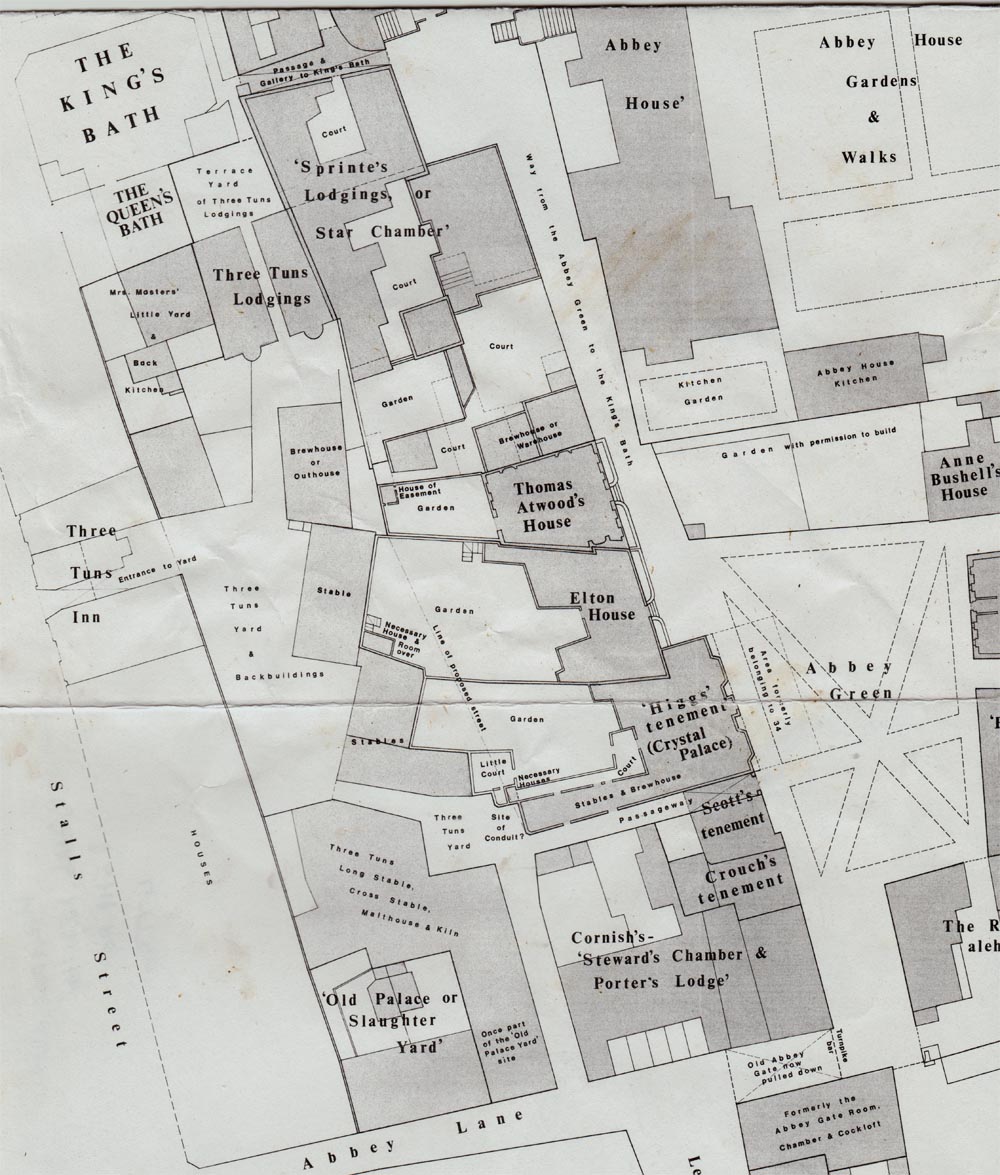

The building we see today called the Crystal Palace, opened in 1851 as an Inn and was named after the famous Exhibition held in Hyde Park in that year. It was designed by Thomas Baldwin in 1764 for a Dr.Grant. The architect refaced an earlier edifice in Bath Stone, which was originally constructed in 1610 by the Carpenter, James Cotterell. For much of its early existence it was used as Lodgings for the extensive Three Tuns on Stall street whose massive Yard stretched back behind it. The site was owned by the Dukes of Kingston, although it was descendants of the influential Chapmans who leased it.

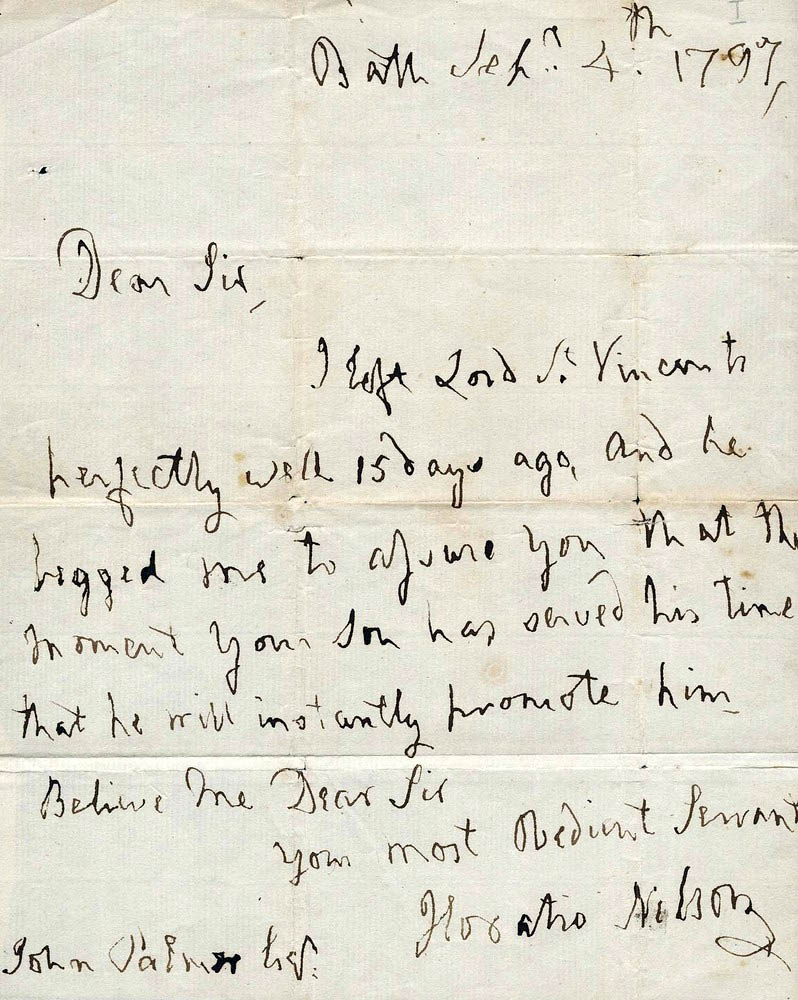

In 1756,the wealthy Apothecary, Richard Harford purchased the lease and resided there until his untimely death seven years later. It was then bought by a Dr. Grant and his family from Scotland who divided it into two parts. They lived in no. 10 and a door at the side, which still exists was for no.11 where they took in Lodgers. After they left it was to remain two separate Lodging Houses, with a Mrs Lloyd and Mrs Norton. The latter was to remain there for over 30 years. She is famous today for charging £2 a week to the naval hero, Horatio Nelson and his wife for their stay in 1783 after the Battle of the Nile.

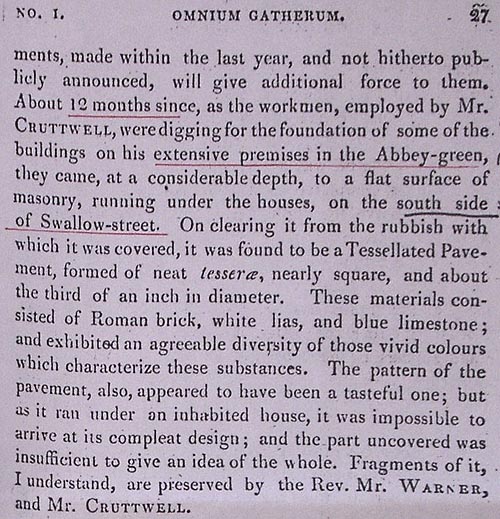

By 1800 it was owned by a Richard Cruttwell who as well as owning the Bath Chronicle and a printing business used the area behind as a Carriers Yard and lived at no. 10. He was there until 1820 when the Carrier business was bought by Charles Tanner who lived with his family in the house facing in to Abbey Green. It was bought by Joshua and Harriet Knight in 1851 who opened it as Public House. They ran their business there for 20 years and in 1872, William McCoombe took on the The family were to remain there until the death of Emily McCoombe in 1934. It was put up for Auction on 13th of August and Russell’s Brewers from Rode paid £3050 for it. The following year they demolished the top floor , where the previous owners brewed their beer, as it was no longer needed. It was the landlord, Rob Wain, who in 1981 was to find a Roman Mosaic in the Cellar and was to become a Celebrity as a result. It has changed hands a number of times since and is now run by the Brewers, Fullers.

.jpg)

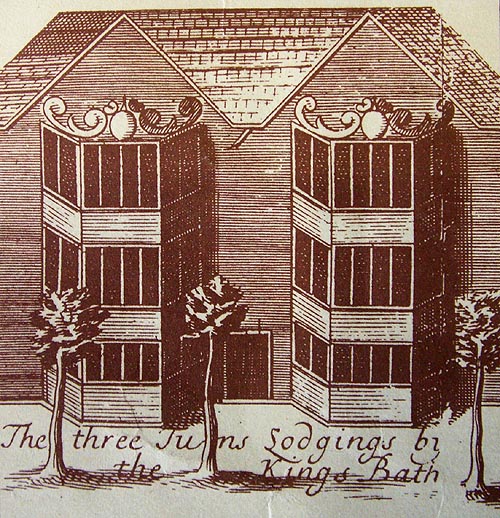

An elongated view of the 3 Tuns Lodgings as they looked in 1785 with the passage way underneath 9 Abbey Green (Mignon House) now covered in with a side window to the passage.

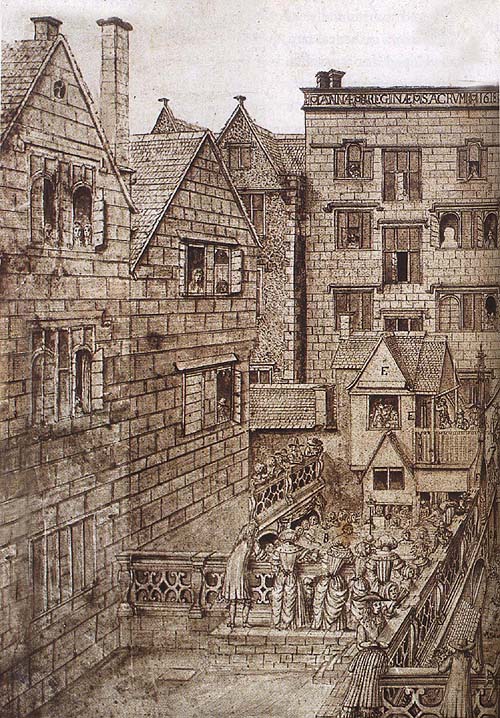

The last building (10) which Johnson shows round the King's Bath is part of the Three Tuns Lodging. Through the middle of this lodging (and just off the picture) a way led out of the yard of the Three Tuns Inn into the small open area shown in the left foreground of the picture. Johnson has here used a certain artistic licence and omitted the low building at the corner of the Bath which, if included, would have obscured the view of the Queen's Bath. For the same reason he has lowered Sir Francis Stonor's balustrade along the south side of the King's Bath which, in both Schellinks' and Dingley's drawings, appears built at a higher level than on the other three sides.

The Three Tuns Inn, the largest property in Stall Street with 33 fireplaces in 1654, had a covered entrance leading through the middle to a large yard with stables and outbuildings. This yard could also be approached from Abbeygate Street and through a six-feet-wide passage from Abbey Green. The Three Tuns yard ran north to south behind the Inn and other Stall Street houses. At the north end of it stood the Three Tuns Lodging. The still standing western wall of the old Priory divided the yard from the back of the Stall Street houses. The landlord of the Inn therefore held the property (10) on two leases: one from the Corporation and one from the owner of the ex-Priory land which lay behind. In 1669 the landlord was William Landick, one of whose trade tokens bearing that date is amongst the collection belonging to the Bath Royal Scientific and Literary Institution. On one side of the token are three barrels and on the other a facsimile of Landick's signature.

Guidott's informative plan of the King's and Queen's Bath shows the outflow gouts from each of these Baths and their meeting point below the open area between the Three Tuns Lodging (10) and the King's Bath. It is noteworthy that Johnson has drawn what looks like a covered hatch over this same meeting point. The gout from the King's Bath gave a good deal of trouble. The Chamberlain's Accounts have many entries for cleansing and emptying it and in 1664 a boy was made to crawl into it to hack away a large stone. All manner of things were thrown into the Baths. No doubt too the old rags which the bath-guides used to stuff the gouts, and which were left lying about stained yellow and ill-smelling, sometimes disappeared into the outflow contributing to the blockages.

Although Schellinks ignores the Three Tuns Lodging in his drawing it was already in situ by 1654. An entry in the Council Minute Book for that year states that it was agreed that "Philip Sherwood and Mr. George Kennis shall not build a slipp . . . out of the way belonging to the Three Tuns Lodging House next to the Queen's Bath into the same Bath". Permission to make this slip had already been requested six years previously and on this occasion the Council had refused even to put it to the vote. Perhaps Schellinks' omission was for the same reason as that of Johnson mentioned above, namely that he felt it more important to show the whole of William Swallow's lodging (11) which lay behind. William Swallow's Lodging House and Dr Robert Peirce's House (11 and12)

The gable end (11) with the small circular window seen in Schellinks' picture near the far right-hand corner of the King's Bath, together with the wing set back at right angles and perhaps built later, was the historic building known in 1591 as "The Starre Chamber or Dr Sprint's Lodging" and, the following year, as "all those buildinge Roomes late in the tenure of Dr Sprint".30 The wing may have been added between 1592 and 1611 when a lease refers to "all that messuage or Tenement commonly called Sprintes Lodging or Starre Chamber and all those new erected lodgings chambers and rooms thereunto belonging". William Hodnett, gentleman, occupied the house from 1612-" and it was during his time that Queen Anne was said to have stayed there. Hodnett mortgaged the property to Bernard Atkins who took over the lease in 1638. By 1654 the house was occupied by William Swallow whose family remained there into the mid-1700s when it was divided into two parts. During all this while the property was run as a lodging house. It had its own bath-door leading, it seems likely, out of the low building with a sloping roof adjoining the gable end of the main building.

The above house stood, like Dr Peirce's (12), on land previously belonging to the Benedictine Priory or Abbey. This land began ten to fifteen feet back from the east end of the King's Bath. The exact line of the actual precinct wall has not been settled. It was generally taken that the King's Bath lay outside the Priory though in the care of the monks. More recently the Bath Archaeological Trust has postulated that the Bath lay actually within the precinct

walls. While this matter remains unresolved it should be noted that a lease32 of 1591, only fifty-two years after the Dissolution of the Priory, records a highway leading out of the King's Bath into the Abbey towards the dwelling house of Edmond Colthurst (12). This highway, in the vicinity of "the Starre Chamber or Dr Sprint's Lodging", meets with "the wall embattl'd on the west side of the Abbye". Comparison of this lease with later ones of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries33 indicates that this "embat-tl'd wall" may have lain fifty feet to the east of the King's Bath.

Edmond Colthurst's house (afterwards known as Abbey House, Priory House and the Royal Lodging) was the residence of Dr Robert Peirce from 1661 until his death in 1710. As already said, the house was connected to the King's Bath by a covered gallery from which a stairway, known as the Great Stairs, led down through a door opening to the Bath. For these facilities Dr Peirce paid rents to the Corporation of ten shillings and fourpence respectively. On the far side of his house lay a garden and there was a side door into the Abbey Church - very convenient, said Peirce, for brides that limped.

This house (12) lay some hundred and twenty feet back from the east end of the King's Bath. Schellinks has indicated it by the straight roof with a single chimney in the centre back of his picture. It must be said, though, that this roof line is substantially different from the one shown in the picture at the top left of Gilmore's contemporary map. Dr C. Lucas, writing in 1756, the year after the house had been pulled down, describes it as a "rude, irregular Gothic building". He was indignant that it had been concealing all those years the "very elegant Roman Baths and sudatories" that were found beneath.34 It is known that Schellinks made notes and sketches to enable him to finish parts of his drawings later. Pressed as he was for time in Bath, did he fad afterwards the more distant houses at the far end not "^mediately beside the Bath? It is difficult to write in any detail wout the buildings he has only lightly sketched at the east end

. ^though the Italianate one with the pointed roof and arcades ^ tost floor level must be the end of Dr Peirce's covered gallery. 1^131^ Placed building of the same height but less glamor-appearance can be seen in the 1764 print of the King's Bath west end by William Elliot

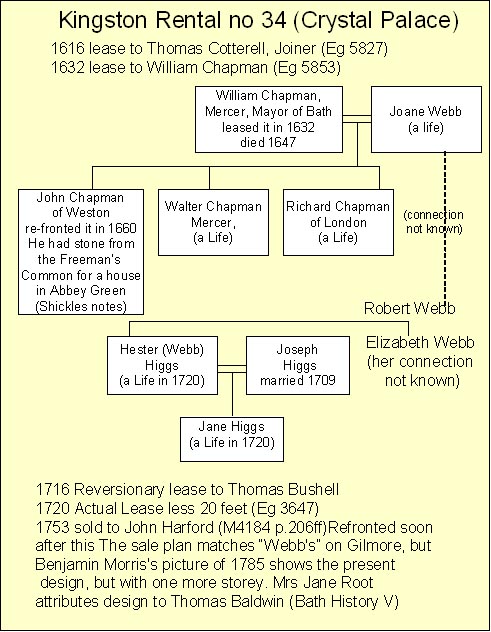

In 1616 this site was let to Thomas Cotterell, joiner, evidently for development, and described as garden ground in the occupation of Robert Evans. By 1632 it was let as a messuage and garden to William Chapman, mercer.

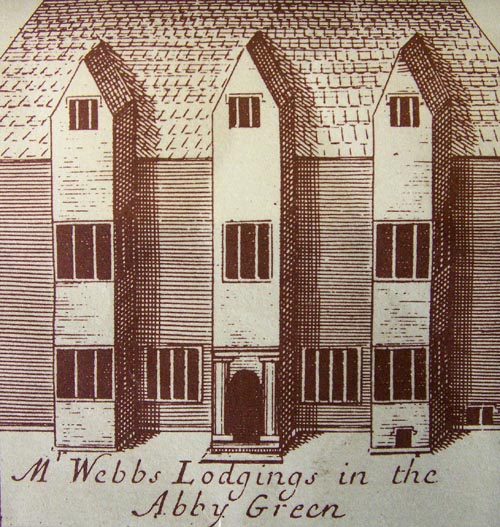

The house appears as "Mr Webbs Lodgings in the Abby Green" in the right-hand bottom border of Gilmore's map. With a central porch and a bay at each side, it appears to match the plan shown here, from M 4184. Gilmore shows the house as set back twenty feet from Speed's site, as described in early 18th century leases. In the Survey of the Manor before John Hall's death, early 18th century, it appears as "Mrs Webb for Higgs". In 1716 Thomas Bushell (leaseholder of the Tuns

Inn) held a lease "for a house late Joseph Higgs in Abby Green". It later passed, like the Tuns, to Harrington and Hull. The property was bought by John Harford, apothecary, in 1753. A plan of 1816 shows the west side of the plot as "Cruttwell's Wagon Yard". The site is now the Crystal Palace.

The

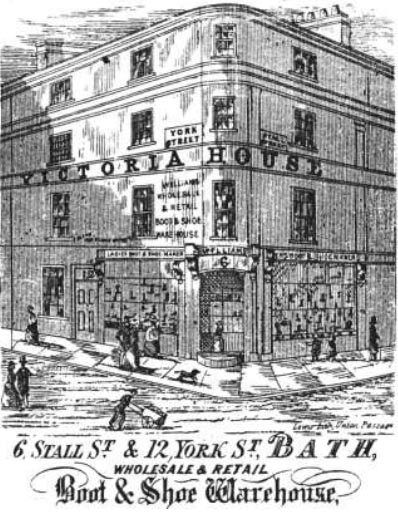

Three Tuns entrance on to Stall Street in 1694

Mr

Webbs Lodgings as depicted by Gilmour in 1694

(now the Crystal Palace)

(now the Crystal Palace)

.jpg)

Rg Ch, 5829. 2 October 1616 John Hall to John Blackleache. Premises of the Tuns Lodgings, speaks of the "Watering Place" as being "West" of the new way, and the rest as being Heath's garden, This would make Thomas Cotterell`s land = Heath's Garden, However Speed drew conduits as boxes (see St. M`s, High Street) and his drawing … ought to = the Little Conduit House of Thomas Cotterell`s Lease.

Red Shaded Area: what is presumed to be the backside of one of the 3 messuages that went with Eg 5829. (Ann Leyton's backside, (see 5827) presumably added to 34 after 1729 when it gave up 20 feet.When John Harford bought the site from the Duke of Kingston in 1753, the layout of the sale plan matched the front of "Mr. Webb`s Lodgings in the Abby Green" of Gilmour`s Map. It seems likely that the redevelopment was done by Thomas Baldwin and was created between that date and Benjamin Morris`s picture of c. 1785. The first lease for building on the site after the dissolution is one for John Hall to Thomas Cotterell, joiner, in 1616 ( Egerton Charters 5827). It seems likely that he put up a timber-frame house, possibly reface3d in stone by John Chapman of Weston in 1660, becoming "Webb`s". At present our theory is that it had the garden in front, between it and the land of the Green, like the Garden house on the other side (the site of North Parade Buildings). This would make it easy for Thomas Bushell to give up twenty feet in front, as he had to do by 1720. He seems to have compensated the house by giving it its garden at the back from land once belongingto the Tuns stables.

To be sold, an Inn called the Three Tuns in the City of Bath; together with the coach house and stables ... in possession of Mr Joseph Phillott ... also a Messuage call'd the Three Tuns Lodging, and also a messuage in the Abbey Green in the possession of Rebecca Salmon.

closed around 1935 and the top floor was removed, its roof marks can still be seen on the gable end of the building next door. Legend has it that, while digging a well in the back yard to supply the brewery with water, workmen tapped into a hot spring, which was capped on the understanding that the Corporation would lay on a free supply of cold water.

The 1903 report on the Crystal Palace described it as having a glass room, a tap room and a drinks bar. At the back was a skittle alley and a private yard with a passage leading to Swallow Street.

In 1951 Bert Oliver, who had been a stocktaker at Fussell's Brewery in Frome, took over the licence.

The southern front of the Tuns Lodgings can be seen in Gilmore's map, left-hand bottom border, and the northern in Johnson's and William Elliott's pictures of the King's Bath. Dr. Leyson (Leason, Lyson etc.) evidently held the lodgings at the beginning of the 17th century. By 1616 the owners of the Tuns Inn in Stalls Street took over the lease for it and the land south, while Leyson's widow was offered a place in St. John's hospice. The Tuns also secured rights of way to Abbey Lane and the Abbey Green. In 1750 Hull and Harrington, leaseholders of the Tuns Inn itself, are listed for 31.

The courtyard north of the Tuns Lodgings seems to have belonged in the early stages to the Mayor and Corporation. This is not definitely established yet.

The stabling complex was replaced by Swallow Street following the agreement of 1808. The site of the Tuns Lodgings is now within the Museum premises.

Medieval deeds refer to the land east of Stalls Street as the Bishop's court. A study of the Bishop's premises is being prepared by the Survey of Old Bath.

Promoted to Rear Admiral and made a Knight of the Bath, Nelson had now established himself as a man of property. His father died in Bath in 1802. Fanny was severely ill in 1805. She received news of Trafalgar as she arrived in the city for the cure. She continued to visit the city until 1815. Nelson eventually lived in Merton House, Wimbledon near London with his daughter and his 'companion' dearest Emma Hamilton, possibly his only real personal success.

amputation, recommended that Nelson see a London surgeon better qualified than he; consul tat ion cost a guinea. Impressed by his patient. Falconer's wife later related to Fanny that, had he been single he would have signed up to join Nelson. His surgeon, Mr Nicolls at 14 Queen Square, quite close to the Nelson lodgings, dressed the wound daily while Nelson was in Bath. Its apothecary was Nelson's former landlord Joseph Spry of 2 Pierrepont Street.

It be wound, according to the practice by which Nelson's arm was amputated, was to leave the "long silk ligatures hanging out of the wound after the operation, so that as suppuration took place and the ligatures separated by necrosis and granulation, they could be pulled out the second or fourth weeks' says Surgeon Commander Pugh in A'p/son and his Surgeons. There is a lot of discussion as to the best technique, with various opinions offered, suffice it to say that, thankfully. Nelson survived and was a testament to the surgeon Thomas Eshelby and subsequent after-care.

Fanny at last could nurse her beloved husband, who ensured she could dress his wound and act as his secretary. Writing with his left hand to Earl St Vintent following the raid on Santa Cruz, he described his lot: ' A left-handed Admiral will never again be considered useful, therefore the sooner I gel to a very humble cottage the better, and make room for a better man to serve the State'. To give the re-united couple some privacy, his father Edmund had arranged lodgings in Chailes Street just around the corner now that New King Street was getting quite full. Along with his sister, William Nelson hurried over from Norfolk to see his brother, as announced in the Bath Chronicle, Nelson wrote with his left hand a letter of acceptance lo the Bath Corporation for the Freedom of the City, and strangely an editorial appears in the Chronicle addressed to 'Nurses, Parents and Guardians a petition by Nelson's Left hand, that you are not a lost cause with only one arm'. Earlier in the year the flag officers at the Battle of Cape St Vincent were made Freemen of the City: Admiral Sir John Jervis, Vice Admiral Waldegrave. Vice Admiral Thompson. Rear Admiral Parker and Commodore Nelson. This entitled them all to a pension of £25 per year. Nelson was offered the Freedom of mam cities, such as Bristol but, as with Bath, never collected it-Nelson spent two weeks in Bath, before setting out for London. He had an audience with the King, being presented by Admiral Earl 11 owe, to be invested \s Ith "the red sash' of a Knight Companion of the Order of the Bath, and he re<ei\ed the Freedom of the City of London from John Wilkes of 'Liberty' fame. Now famous, he was much in demand by artists, in particular he sat for the painter Lemuel Abbot and the sculptor Lawrence Gahagan. He attended a service of Thanksgiving at St Paul's Cathedral with the Royal Family lor the recent victories at sea. By the middle of December his wound had sufficiently healed for the Royal College of Surgeons o pass him fit to be appointed to a new vessel, and he was eager to rejoin John Jervis, now ennobled as Earl St Vincent, and return to sea. He wrote to his Captain. Edward Berry, to 'speedily marry or Mrs Berry will have little of your company.'

The topic (hat had dominated Nelson's correspondence with Fanny while at sea was to fix somewhere of their own to live. Susannah Bolton's brother-in-law Sam had found a suitable property which Fanny and Nelson drove from London to view. The 'little cottage', in (act Roundwood Farm comprising nearly 60 acres, near Ipswich, was quickly bought by Nelson for £2000. The papers were signed in November 1797 and witnessed by Captain Berry, but the tenant still had six months of tenancy to run before they could take possession of the house.

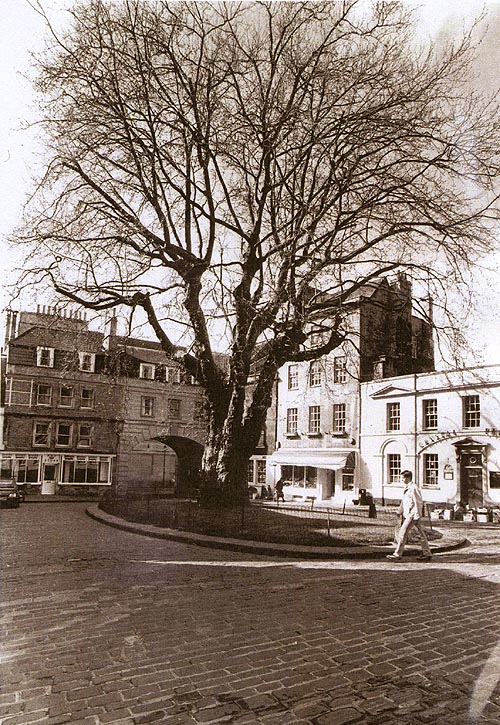

In 1798 the smoke of London proved too much for Fanny, and so they returned to Bath in January for a two week holiday while awaiting the preparation of the I'aiiguard. They lodged in 11 Abbey Green (now part of the Crystal Palace public house); the proprietor was a Mrs Norton who charged 10s 6d (52'/*p) a week and 5s 6d (27'Ap) for servants. The only remnant from this period is possibly the Georgian grate in the Lounge bar of the Crystal Palace. The magnificent 'plane' tree in the centre of ihe square Nelson would have know n.

The Nelsons look full advantage ot the pleasures of Bath. Nelson writes of the pleasure of attending ihe Theatre Royal, Orchard Street. Taking Earl Lansdowne's plate in Mr Palmer's box, he wrote, "his Lordship did not tell me all its charms, that generally some of ihe most handsomest ladies in Bath are partakers in the box. and was I a bachelor I would not answer for being tempted: but I am possessed of everything which is valuable in a wife, I have no occasion to think beyond a pretty face'. Nelson goes on to mention how, although there was a Fund for the present war, he felt his contribution would be to 'debar myself of many comforts to serve my Country, and 1 expect great consolation every time I cut a slice of salt beef instead of mutton*. Other attractions were the Assembly Rooms to play cards, concerts or Balls, but much ot the time was spent paying social calls and catching up on relatives.

Across the way from [heir lodgings lived Admiral Samuel Barrington at I Abbey Green, a good friend of both Nelson and Fanny, who they knew from their time in the West Indies. Barrmgton was a contemporary oFJohn Jervis, the two of them as young officers had surveyed all the major naval ports of the Baltic, North Sea and Mediterranean. Samuel Barrington's cousin, Mr Daines Barrington, a naturalist, was instrumental in the Admiralty's expedition u> the Arctic of the bomb vessels Carrass and Racehorse, when Nelson had served as coxswain in his Captain's gig.

Little is recorded in their correspondence of their activities, the stay lasted three weeks. Fanny returned later to Bath for a further few months staying with Edmund to sort out their effects that were held in storage in Bath at Wiltshire's 'near the old Bridge', for removal to their new home in Ipswich. Her household consisted of, 'an old Catholic cook near 60 years ol age, a girl of fourteen and Will' . She dined with Captain Phillip and his wife, who had commanded the first fleet to Australia, both good friends of the Xelsons. Edmund sent Nelson items down on the wagon to Portsmouth from the Angel Inn, Bath.

In March 1798 Nelson returned to Portsmouth and his new command, Vanguard. In a letter to Fanny he tells her to check the weather vane on the roof of St Mary's chapel in Queen Square (now demolished but it stood on the south-west corner; a small colonnaded monument now marks the spot) to see whether he had sailed. Departure delayed through contrary winds, Nelson checked his wife's packing which, much to his frustration, did not seem to match the lists accompanying his chests. He was short of socks, stocks and small amounts of gold, and in fact had to send ashore for more clothes which, much to his disdain, were double the price of the originals. Eventually, at the beginning of April, he set sail for Portugal.The next Bath heard of Nelson's exploits, as in London, was in October 1798, with the news of the victory on 1 August at the Battle of the Nile and the defeat of the French Fleet. A collection was made for orphans and widows, reported in the Bath Journal of 15 October, the Guildhall and lending libraries: Bull's. Baratt's, Mevler, Bally's, Marshall's, Brown's, Hazard's, amounting to £453.9s.4d. In Bath the celebrations were suitably patriotic and reported in November: 'At the particular request of the Magistrates, the inhabitants did not illuminate their houses on the evening of Wednesday last, but the joy that displayed itself by every other means is not to be described - gilt laurels, elegant ribbons with appropriate muttos, appeared in every bosom. The mayor gave an elegant cold collation at the hall with a general in\Station to the whole corps of Bath volunteers and to the inhabitants at large, when the greatest harmony prevailed to a later hour. The mayor's toast was given with the most enthusiastic bursts of approbation and loyalty

The Three Tuns started out in the late sixteenth century as an alehouse built up against the wall of the Abbey precincts - roughly where Swallow Street is today. The tenant of the house, Philip Sherwood, had "a post thrust out of the wall of the house and thereon a little sign of three tunns hanging, resembling the sign of an alehouse." In 1620, he obtained a licence from Sir Giles Mompesson to turn his alehouse into an inn, "whereupon he set a new fair sign of three

is, and fixed to support it two great posts in the…..

revoked his licence on a technicality. This may have been part of a campaign to suppress unnecessary drinking establishments, but is more likely to have been an attempt by the Chapman family, who not only owned Bath's biggest inns but were also influential councillors, to stifle competition.

Sherwood called the Corporation's bluff and "refused contemptuously to take down his sign." The Corporation sent the bailiffs round to remove it, only to be confronted by Sherwood's son "with a loaded weapon and a maidservant with gunpowder." When a crowd of around 300 people turned up to see what would happen next, the bailiffs withdrew, only to return when things had quietened down to complete their task.

The next day, Philip Sherwood put his sign back and filed a complaint with the Privy Council. Even though they upheld the Corporation's opposition to the inn and the "sundry disorders" that had occurred there, the Three Tuns stayed open. Its proximity to the King's Bath soon made it popular with those coming to immerse themselves in the waters. A diary from 1634, preserved in the British Museum, records the arrival of some officers from Wells:

To this Citty we came late and wet and entred stumbling . . . over a fayre archt Bridge crossing Avon ... and heere we billetted our Selves at the 3 Tuns close by the King's Bath - And now prepared wee with the skillfull directions of our Ancient to take a Preparative to fit our jumbled weary Corps to enter and take refreshment in those admired, unparalelld medicinable sulphureous hot Bathes."

In 1632, Philip Sherwood was elected to the council and thereafter regularly supplied goods to the Corporation. In 1640, for example, he supplied a "pottle of sack which was brought to the hall." In the following year he provided the Recorder with "lodging, fier and beare." He had clearly patched up any disagreement with the Chapmans and during the Civil War served under Henry Chapman, the landlord of the Sun in the Market Place, as the Lieutenant of the Bath Trained Bands.

In 1666, the Three Tuns was leased from the Corporation by a Mr Smeaton. The lease passed to William Sherston in 1679 and to Richard Ford, an apothecary, in 1719. Its dimensions in 1719 were recorded as 18 feet 3 inches by 16 feet 4 inches. Clearly, this was just the original alehouse. When Philip Sherwood turned it into an inn, he had not expanded the original property, but acquired buildings nearby to use as lodgings and dining rooms. A new dining room was added around 1718, for in September that year, Dr Claver Morris of Wells recorded in his diary,

We continued at Bath. I was called in to Mr Harington at Kelston. I got Mr Du Burg, Mr Shojan, Mr Walter, and Mr David Baswiwaldt to go with me. We dined there, and had a Consort of Musick. We returned to Bath in the evening, and 1 entertained them with 3 fowles and wine in the great new drawing room at the Three Tuns, where I had a performance of Musick by these extraordinary hands.

The adjacent buildings were still not formally regarded as part of the inn in the mid-eighteenth century, as an advertisement from the Bath Journal of 1748 indicates:

The Three Tuns Inn &Javern to be sold, in the city of Bath together with the coach houses and stables thereto belonging. And also a messuage called the Three Tuns Lodgings, and a House and Garden in the Abbey Green.

The property in Abbey Green later became the Crystal Palace. A further advertisement appeared on 10 October 1748:

To be sold, an Inn called the Three Tuns in the City of Bath; together with the coach house and stables ... in possession of Mr Joseph Phillott ... also a Messuage call'd the Three Tuns Lodging, and also a messuage in the Abbey Green in the possession of Rebecca Salmon.

Joseph Phillott, the grandson of a French immigrant, was at the Three Tuns till 1767, when he left to take over the Bear in Cheap Street. His place was taken by Abraham Eve. The Three Tuns was a favourite meeting place for friendly and benevolent societies in the late eighteenth century. In 1778, for example, the Friendly Brothers of the Bath Knot and the Brothers of the Ancient & Most Benevolent Order of the Friendly Brothers of St Patrick used it as their headquarters.

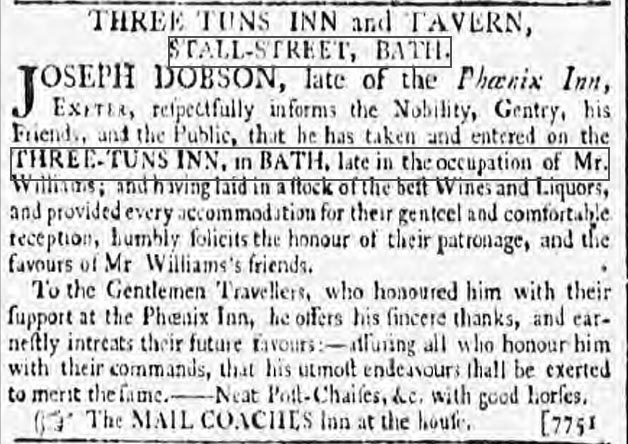

In 1774, Henry Phillips from the Saracen's Head took over the Three Tuns. He, in turn was replaced by J Williams from Beckhampton in 1783. The following year, when the mailcoach service was introduced, the Three Tuns was chosen as its depot in Bath. On 4 August 1784, the Bath Chronicle reported that

the new mail diligence set off from Bristol on Monday last for the first time at four o'clock and from the Three Tuns in this city at twenty minutes after five the same evening. From London it set out at eight on Monday evening and was in Bath by nine the next morning.

Shortly afterwards Joseph Dobson took over the Three Tuns. In 1789, he disposed of the Coach, Chaise and Stabling Business to Henry Phillips (who had been the landlord from 1774 to 1783), but kept the Inn and Tavern on. As coaching businesses mushroomed in size towards the end of the eighteenth century, there was an increasing tendency for them to be run and owned separately from the inns in which they had started off. At around this time, the Three Tuns increased its capacity by taking over the coachyard of the old Bell Inn in Bell Tree Lane.

In 1792, the Three Tuns was taken over by Henry Ballanger from the Greyhound & Shakespeare in the Market Place. Five years later he died and the business was carried on by his widow. Early in 1799 Elizabeth Ballanger married John Reidford. She kept her former name, however, and, on 5 April 1804, put a notice in the Bath Chronicle, thanking all those who had supported her "during fourteen years residence" at the Three Tuns, but adding that the inn was now closed. The Three Tuns Inn, set up over 170 years earlier in the teeth of official opposition, and the stopping place for the first mailcoaches through the city, had slipped quietly into history.

Eight years later, it was demolished, In 1812, Thomas Parfet, who was responsible for rebuilding much of Stall Street, leased "the plot of ground where the Three Tuns stands on the.east side of Stall Street, [to] build three good stone messuages thereon, fronting Stall Street, and two fronting York Street. A licence to sell ale was not guaranteed." However, one of the buildings built on the site of the old Three Tuns did reopen as a pub, albeit briefly. In 1830, John Rudman was listed as the landlord of a new Three Tuns in Stall Street. The new inn was taken over by Joseph Claxton in 1839, but closed in the late 1840s.

Despite its early demise, in its heyday the Three Tuns was one of Bath's best-loved and most boisterous inns, as Smollett's description of an evening spent there in the company of the great Shakespearian actor James Quin (1693-1766) makes abundantly clear:

I had hopes of seeing Quin in his hours of elevation at the tavern, which is the temple of mirth and good fellowship; where he, as priest of Comus, utters the inspirations of wit and humour. I have had that satisfaction. I have dined with him at his club at the Three Tuns, and had the honour to sit him out. At half an hour past eight in the evening, he was carried home with six good bottles of claret under his belt; and it being then Friday, he gave orders that he should not be disturbed till Sunday at noon. You must not imagine that this dose had any other effect upon his conversation, but that of making it more extravagantly entertaining. He had lost the use of his limbs, indeed, ' '

several hours before we parted, but he retained all his other faculties in perfection; and, as he gave vent to every whimsical idea as it rose, I was really astonished at the brilliancy of his thoughts, and the force of his expression

The Three Tuns also played a minor part in one of eighteenth-century Bath's most shameful episodes. One night in 1778, the French Count and Countess du Barre, were playing cards with an Irish gentleman called Count Rice at their lodging in the Royal Crescent:

At length a violent disagreement took place between the two Counts, and each being of an impetuous disposition, it was resolved that the dispute should terminate with the death of one or both. Accordingly, they left their abode about one o'clock in the morning, procured a coach from the Three Tuns in Stall Street; and provided with arms, seconds, and surgical assistance, reached Claverton Down long before daybreak. There they paced in sullen silence till dawn began to break, when their stations were taken. Count Rice fired but his ball did not take effect. Du Barre returned the fire, and the ball lodged in the groin of his antagonist, who fell; but raising himself immediately from the ground, he discharged his second pistol in a recumbent position, the contents of which penetrated the heart of the unfortunate Du Barre. The parties decamped, and the body of the deceased, Du Barre, was left on the field of battle for more than twenty-four hours, an object of curiosity to those who could patiently and calmly witness so horrid a spectacle. The wounded survivor was taken to the York House, and Monsieur Du Barre was afterwards buried at Bathampton, where a stone now marks the spot of his interment. Count Rice recovered, was tried at theTaunton assizes, in 1779, and acquitted.

The death of the Countess, 15 years later, was even more terrible. Arrested by the French revolutionary government for carrying a picture of Mr Pitt, the British Prime Minister, she was sentenced to the guillotine:

On her passage to the scaffold, she leaned on the head of her attendant, and appeared almost dead; but when she reached the fatal spot, the sight of the instrument of death rallied her fainting spirits. Suddenly she rose up and rent the air with shrieks, her convulsed frame acquired most extraordinary strength; and, after a conflict with her executioners, at the relation of which humanity shudders, the fatal stroke released her from all her sufferings.

The Crystal Palace opened in the old lodging house of the Three Tuns in 1851 or 1852, its name commemorating the Great Exhibition held at the Crystal Palace. The wood panelling in the bar of No 10 (where Nelson is believed to have stayed) was salvaged from the old Three Tuns when it was demolished.

closed around 1935 and the top floor was removed, its roof marks can still be seen on the gable end of the building next door. Legend has it that, while digging a well in the back yard to supply the brewery with water, workmen tapped into a hot spring, which was capped on the understanding that the Corporation would lay on a free supply of cold water.

The 1903 report on the Crystal Palace described it as having a glass room, a tap room and a drinks bar. At the back was a skittle alley and a private yard with a passage leading to Swallow Street.

In 1951 Bert Oliver, who had been a stocktaker at Fussell's Brewery in Frame, took over the licence. Food had been a staple of many pubs in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but in the twentieth it had fallen by the wayside. Bert Oliver was one of the first publicans in Bath to start serving food again, rustling up delicacies such as fillet steak and chips for 5/6 (27.5p). When he left, Bass sold the pub to Eldridge Pope, the Dorchester Brewers, and Roy Wain became the new licensee. He soon became a celebrity when he uncovered several skeletons and a Roman mosaic in the cellar. It was decided not to try to move the mosaic, but to preserve it underneath a layer of polythene and sand, where it remains today.

Imaginatively revamped, with aTitchmarsh-inspired garden at the back, complete with decking, gazebo and cold-water fountain, the Crystal Palace is a popular oasis in the heart of the city.

The Three Tuns on the corner of Stall Street as it appeared in 1805 to Thomas Rowlandson.