Charmouth`s Pirate Parson -

Rev. John Audain (1755-1825).

Rev. John Audain (1755-1825).

St. Andrews Church is very fortunate today in having one of the finest 18th century marble memorials in the country. It stands to the left of the Altar and commemorates the life of Anthony Ellesdon, Village Squire, who lived to the fine old age of 79 and died in 1737. It was commissioned by his nephew Richard Henvill, A Bristol Merchant, who inherited the manor of Charmouth from him. High above is a beautiful baroque memorial to William Ellesdon, father of Anthony who bought the Manor in 1648 and was famous for assisting King Charles II in his attempt to escape through Charmouth to France. The village Rector at that time was Bartholomew Wesley, Great Grandfather of the famous, John Wesley. We will be covering their colourful lives in the first part of the talk. We will then go on to the debauched life of the Rev. John Audain who was to become Rector in 1783 and receive its stipend for the next 40 years yet was only briefly here, before returning back to the West Indies and a life as a Slave Trader, Smuggler, Privateer and Bigamist.

George Roberts wrote a comprehensive history of Lyme Regis and Charmouth in 1834. He gave a detailed description of the old Church, then known as St. Matthews. as follows:

In the chancel are several monuments. One is to the memory of Anthony Ellesdon, the last of that name, who died 13th November 1737, aged 79, erected by Richard Henvill, to whom the property went in default of male issue. He was a benefactor to the church, as appears by an inscription on the north wall, around the arms of Ellesdon, “Re-edifyed and beautified by Anthony Ellesdon, Esq., 1732.”

Rev. Mr. Bragge, M.A., late Rector , on March 3rd, 1769, aged 68.Arms of a chevron gules between three bulls, passant regardant, sable. A pretty design in the memory of master Joseph Hodges.

He goes on to write that "In the churchyard, on a raised tomb, much defaced, Mrs. Margaret Stuckey, the daughter of John Limbry.

On a large tomb, railed in, to the memory of James Warden,Esq., who fell in a duel the 28th of April, 1792, in the 56th year of his age”. This slide shows the former Church as it would have looked then from a model made by William Hoare just before it was demolished and rebuilt in 1836.

It is astonishing to think that we still have all these fine monuments in St. Andrews today, thanks to the famous architect, Charles Fowler, who ensured that they were incorporated into his new church in 1836. The watercolour was painted by Charmouth Artist, Galpin Carter shortly after the new church was opened. By the doorway is the tomb for James Warden and behind the group is that to the Limbry family, still in the same position today.

We will begin with the Ellesdons who were one of the leading families in Lyme Regis before moving to Charmouth in 1649 on buying the Manor. They were successful merchants and were regularly Mayors of the borough, appearing sixteen times on the list from generation to generation. The earliest is Ralph Ellesdon in 1521 and the last is in 1659 with John Ellesdon, whose brother, William by then had moved to Charmouth. The illustration shown here dating from 1539 is the earliest view of both Lyme Regis and Charmouth, with their beacons on the peaks of Golden Cap and Timber Hill. The depiction of our church is fairly accurate with its high spire and the Cobb a distance from the shore at Lyme Regis at that time. Thomas Ellesdon was a leading merchant in that year and Mayor of the borough, for which he stood four times. Other members of the family were also members of parliament for the borough over the years.

Lyme Regis was an important port in Tudor Times. It enjoyed a long heyday between 1500 and 1700. The town was able to offer 23 ships out of a total for Dorset of 61 vessels at the time of the Armada. By 1600 it was carrying on a lucrative and far flung trade not only to the Mediterranean, but also Africa, to the West Indies and the Americas. The Merchants such as the Ellesdons grew very rich. One of these was Sir George Summers, the discoverer of Bermuda who lived nearby to Charmouth at Berne Manor. The slide gives us a taste of how Lyme and its citizens may have looked in that period.

This is one of the earliest engravings of Lyme Regis by Willliam Stuckeley which dates from 1723, when the Cobb can be clearly seen as detached from the land which it remained until 1756. In the distance is Charmouth, then a small village, whose main trade was the making of Sail cloths and farming.

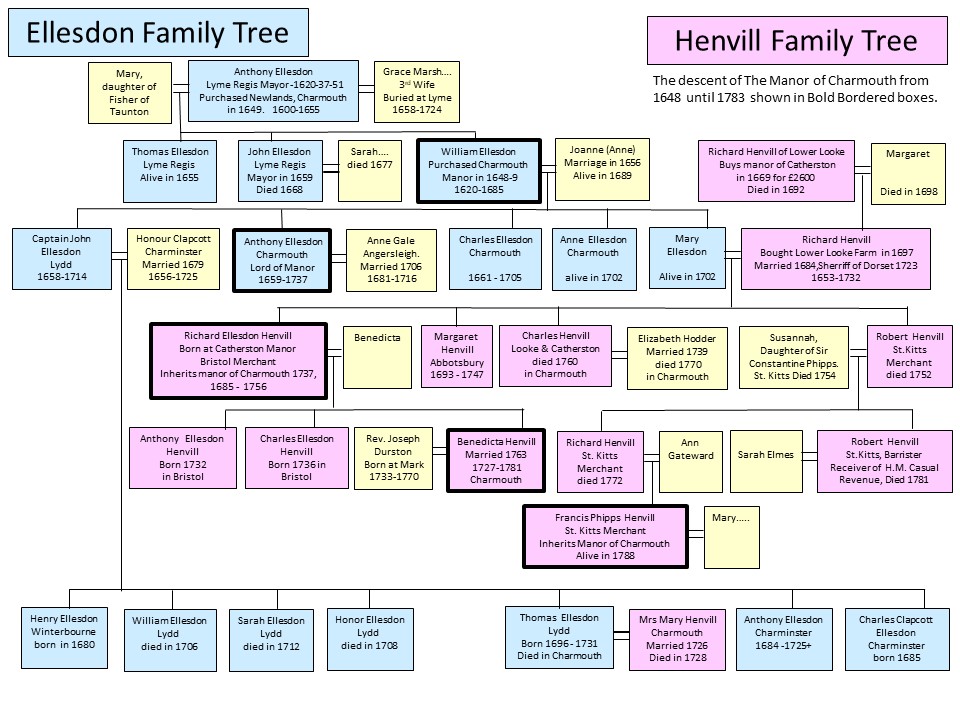

Hutchins in his "History of Dorset" included the family tree in recognition of their importance, which is shown here. We have underlined the leading members from Ralph in 1521 to Anthony whose fine memorials we still possess in St. Andrews.

St. Michaels Church in Lyme Regis has a magnificent Brass Memorial to the family which corresponds to the family tree shown on the previous slide with its descent from Ralph to Anthony, the father of John who remained in Lyme Regis and William who moved to Charmouth during the Civil war. Their importance in the governing of the town is revealed in the verse:

" Men pious just and wise, each many a year

the helm of this town government did steer.

Beyond base envious reach, whose endless name

lies in all those that emulate their fame".

.jpg)

The family owned a large house in Church Street opposite St. Michaels Church. It was here that William and his brother John were to be bought up by their parents Grace and Anthony. John`s life was to be spent in Lyme Regis where he was to eventually become its Mayor in 1659.He died relatively young in 1668 and bequeathed his estate to his brother, William. A copy of his Will has survived and an abstract is shown in which his wife writes "Be it known to all that Sarah Ellesdon, the Relict of John Ellesdon, late of Lyme Regis do herby relinquish all my right in the personal estate of my deceased husband and now devise the letters of administration may be granted to his natural brother William Ellesdon, Gent. Signed Sarah Ellesdon". It is difficult to pinpoint exactly where he lived, but it may well have been "Monmouth House" whose interior today is shown on this slide with its fine coffered ceiling and fireplace.

On the same street was the entrance to the George Hotel, which was completely destroyed in a fire in 1844. George`s Square is all that remains of this Inn made famous by the fact that The Duke of Monmouth used it as a base in 1685. The slide shows an artist’s impression of how it may have once looked at that time.

The Civil War was to divide many families, no more so than the Ellesdons. They had been staunch Royalists in a town that supported the Parliamentarians. In the year of 1644, the considerable importance of Lyme led to it being besieged by Prince Maurice and the Royalist Army. They heavily outnumbered the Parliamentary forces in the town. But the town held on for two months with supplies from the sea until the Royalists left. The leading member of the Ellesdons at that time was Anthony who had earlier stood as Mayor. It was he who was to purchase in 1649 Newlands Manor on the edge of Charmouth. The same year his son William bought Charmouth Manor. His brother, John remained in Lyme Regis and was known to support Cromwell, for there is a later letter from Col. Robert Mohun "setting forth articles against John Ellesden, who was put into the place of Collector of Customs of Lyme by Cromwell". His support must have created divided loyalties with his brother. William rose to the rank of Captain in the Royalist Army and fought in a number of battles for them.

The royalists were finally defeated at the battle of Worcester on the 3rd September,1651 and the young Charles who was to become King attempted to flee the country from there to the coast and liberty in France. His route across country was very hazardous and even though in disguise he narrowly missed capture. There was the famous occasion when he had to hide in an Oak Tree at Boscabel with his enemy just below him.

.jpg)

This episode was forever more to be commemorated in a number of Inns named "Royal Oak" of which Charmouth is possessed of one. The Inn sign depicts the large stone just outside Bridport that shows the road that was taken by King Charles to escape his enemies.

By September 17th, 1651 King Charles was known to be hiding at Trent, on the outskirts of Sherborne in the Manor owned by the Wyndham family. They told the King that Captain William Ellesdon of Charmouth had already successfully assisted in the escape of Lord Berkley to the continent. A meeting was arranged with him and a plan was put in place for the King to stay in a house owned by his father at Monkton Wylde, which is still called Elsdons after them. A slide of the farm house today is shown here, with its plaque commemorating the visit. William had arranged that Stephen Limbry, who was a sailor and also a tenant of his would take the King to a ship moored off the coast from Charmouth Beach. The King was to come to Charmouth and spend the night in what was then “The Queens Armes” but today “The Abbots House”.

.jpg)

This engraving shows us how The Queens Armes once looked and as it today. It was already ancient by the time the King stayed there as it had formerly been the Stewards House, when the village was owned from the 13th century by the Abbott of Forde.

In 1951 Charmouth and Wootton Fitzpaine Conservatives re-enacted Charles II attempt at escape from Charmouth for the 300th anniversary of the event. They printed a special booklet from which this photo was taken. Many of the village played parts in it.

Stephen Limbry had returned home before the meeting and his wife had her suspicions of his late night trip out to sea after visiting the Market in Lyme Regis earlier in the day and seeing the posters with a reward of £1000 for information leading to the capture of King Charles II as shown in the slide. It was likely that the King and anyone helping him would have been executed for treason if caught. She with her two daughters locked her husband in a closet for fear of his involvement and by the time he was let out the King had decided he could wait no longer and took the road to Bridport, where he was nearly captured and after a week away returned back to the safety of Trent.

.jpg)

Trent Manor, where King Charles was in hiding, as it would have appeared at the time. The photograph at the top is of the house which is still standing near the church in this pretty village, just outside Sherborne.

.jpg)

King Charles II finally left these shores near Shoreham on October 15th, after a long and tortuous journey across country. The map shows the route taken by him. William Ellesdon of C harmouth,wrote a detailed account of the event which is still to be seen at The Bodleian Library in Oxford which was used by Lord Clarendon for his "History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England".

Sir John Pole was Lord of the Manor of Charmouth at the beginning of the Civil War. He had sided with Parliament and in 1643 had twice helped to lead anti-royalist raids in Devon and Cornwall. His position in Devon was complicated by his son William ' s decision to fight for the King, and both Colcombe Castle and Shute Barton, shown here, were badly damaged during the war, by royalist and parliamentarian forces respectively. He died in April 1658, and was buried at Colyton, where he had erected a lavish monument to himself and his first wife. Although he was to sell the Manor of Charmouth to William Ellesdon in 1648, he retained The Mill and 35 acres of land in the village, which was eventually to be sold by his descendants at the end of the 18th. Century.

Chideock Castle was another casualty like Colcombe and Shute Barton of the Civil War. The castle was standing when Buck published a drawing of it in 1723. During the war it was taken and retaken several times by each party and in 1645, Colonel Ceely, the Governor of Lyme charged £1 19s. for the work of demolishing it. Little remains today in the field at the bottom of Ruins Lane.

This print shows King Charles II welcome return to this country in 1660. He later visited the village and granted William Ellesdon and two successive heirs a pension of £300 per annum, and presented him with a medal bearing the inscription "Faithful to the Horns of the Altar". The King also gave him a beautiful miniature by Samuel Cooper, together with a pair of silver candlesticks.

The Miniature painting was inherited by descendants of the family and was last recorded in St.Kitts in the West Indies. It would be exiting to locate it as Cooper produced life like paintings as seen in the slide. This one was given to Colonel Careless for assisting the king and shows an oak tree on a gold field with a red fess bearing three royal crowns; the crowns represented the three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. It is very similar to that which would have been given by the King to William Ellesdon.

The pension was for both him and his immediate family and would be derived from taxes received from the port of Lyme Regis. There is a website called British history online that has a huge database covering parliamentary records and almost yearly there are references to those benefitting from his pension and through this have been able to obtain important information about the family. Most intriguing was £1000 he was to receive in 1663 for his work for the King's Secret Service. Unfortunately, the money was often not forthcoming and there are pleas from his family for these outstanding payments. It reveals that he died in 1685, the year of the Monmouth Rebellion, but his pension was to continue to be received by his wife, Joanne and children - Anthony, Charles, Mary and Anne long after.

The silver communion Plate presented by William`s son to the Church in 1717, with the Ellesdons coat of Arms given by King Charles II, which is still in use today at services at St. Andrews.

St. Andrews has one reminder of William Ellesdon who was buried in the church in 1685. It is a baroque marble plaque, high above the more impressive memorial to his son, Anthony. Cleaning it will one day no doubt provide us with an inscription.

William Ellesdon definitely lived at The Manor House opposite the church. The 1664 Hearth Tax listings for the village show him as the owner with 6 hearths, the highest number in Charmouth. The Manor House we see today has been much altered with an additional east wing and refacing in the 19th century. He and his family were the first resident Lords of the Manor and played an important part in village activities. They were also Patrons of the church and owned considerable property in other villages in Dorset.

The interior of the Manor today with the ancient fireplace and over mantel made from part of a carved wooden screen from the former church.

Another claim to fame in the history of St. Andrews Church is the fact that we had as our Rector none other than the great grandfather of John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Church. Bartholomew Wesley became Rector in 1645. He was placed here by the Parliamentarians and supported their cause. His time as Rector coincided with the attempt by the future King Charles II escape by boat to France from the shores of Charmouth in 1651. In the early morning after the Kings departure one of his party’s horses was taken to be shod. The blacksmith declared that its shoes had been made in the north of England. When the Ostler said that a party of strangers had sat up all night, suspicion was aroused. He ran to consult Mr. Wesley at the church, but as he was reading prayers, there was considerable delay, and Charles was gone before any measures could be taken to prevent his escape. Bartholomew Wesley made no secret of his intention to capture the King. He told a friend in jest that if ever Charles came back, he would be certain to love long prayers, because “he would have surely snapt him” if the prayers had been over earlier. The slide shows the Pulpit Barthomlomew preached from whilst at Charmouth, now preserved in Bridport Museum and a painting of his famous great grandson, John Wesley.

Bartholomew was the son of Sir Herbert Wesley, of Westleigh, Devonshire, and Elizabeth de Wellesley, of Dangan, county Meath, in Ireland. He studied medicine and divinity at Oxford and married the daughter of Sir Henry Colley, of Kildare, in 1619. Nothing is known about his history till 1640, when he became Rector of Catherston, near Charmouth. After the Restoration he was ejected from his living in 1662. His skill in medicine, which had formerly enabled him to render signal service to his poor parishioners, now became his sole means of support. For some time after his ejection, Bartholomew Wesley lived quietly among his old parishioners in Charmouth. He cast in his lot with the persecuted Nonconformists, but no violence seems to have been used against a man who had won general respect by his benevolence and his blameless character. He was probably compelled to leave the district after the Five Mile Act was placed on the statute books; but we only know that he did not long survive his son, who died in 1678.

Bartholomew Wesley and his son, John Wesley are shown as signing an indenture for their house sale in 1668. The property now called “Mill View” stands on the site of the former house where they lived. The deeds still exist in the Dorset Record Office and shortly after the Wesleys moved it was bought by the same Stephen Limbry who was involved in the attempted escape of the King. Another reminder of this famous Clergyman is of course Wesley Close which was named after him in more recent times.

Patron of the Church at the time of Bartholomew Wesley was William Ellesdon who had at least 3 sons and 1 daughter. The eldest of these was Anthony, born in 1659 who was to remain in Charmouth and become on his father’s death in 1685, Lord of the Manor. He lived most of his long life in the Manor House opposite the Church. He was well educated and is recorded as attending Wadham College in Oxford, where he received his degree in 1676 and went on to the Inner Temple in London, which he left in 1683.

It would be interesting to see where his loyalties were in 1685 as this was the year of his father’s death, aged 65 and also when The Duke of Monmouth landed nearby to take the throne from King James II. The day after he arrived a group of supporters followed the coastal path through Charmouth on to Bridport where they had a disastrous skirmish with the King’s supporters there. After the Battle of Sedgemoor, Judge Jeffries rounded up his supporters for trial. The list included16 poor souls from Charmouth who were suspected, 2 of these were hanged and 2 more transported. The fine Memorial to Anthony, commissioned by his nephew, Richard Henvill is shown in the slide with the translation n on the right.

The Reverend Edward Bragge was Rector from 1708 until 1747.An interesting insight into his time in Charmouth can be seen in a Survey shown here undertaken by Bishop Secker in 1735 of his Diocese in Dorset. He writes "that it was augmented by Mr. Ellesdon, the Patron and the incumbent Mr. Edward Bragge was a good Tory resident. It was a large Parish about 60 houses. Many Presbyterians and a Meeting House whose teacher was Mr. Robert Batten. No Papists. He remarks that it was a very handsome church". The document below shows Anthony in the year,1707 confirming the appointment of Rev. Edward Bragge on the death of his father Joseph who had been Rector of the village for 30 years. It was he who later built Lutrell House in 1735.The fine memorial in the church records that he was to go on for another 39 years in this position most of that time under the patronage of Anthony Ellesdon.

There is a fine memorial at the rear of the church above the door that leads to the Bell Tower which records how Anthony Ellesdon had re-edified and beautified the church in 1732. This large tablet had previously been placed in the former church and fortunately for us been taken with many other memorials to the rebuilt church on its completion in 1836. He not only spent considerable money on improvements to the Church but gave additional funds to the Rector and was well regarded judging from his epitaph preserved on his memorial.

.jpg)

Most of Anthony's life was to be spent in Charmouth and he is often referred to in Deeds and documents of the time. The one shown here is for a house known as Wades that he gave a lease for 99 years in 1714 to Thomas Thorne of Hawkchurch. In 1706 he married Anne Gale from Angersleigh, near Taunton in Somerset. He would have been 47 in that year and she just 25. They were to have no children and she is recorded in the Parish Records as dying in 1716. Sadly he outlived all his family and his fortune and Estates were to be left to his sister's sons Richard and Charles. His Will shows him owning property in the parishes of Symondsbury, Lytton Cheney, Winterbourne Stapleton and Winterbourne Abbis in Dorset. It also refers to his father in that “I give to Richard Henvill the use of my medal set round with diamonds which was given by his late royal majesty King Charles II to my honoured father for his loyalty to the said king.”

The Henvills came on to the scene in Charmouth when in 1669 Richard Henvill senior of Lower Looke, near Abbotsbury in Dorset purchased from Sir Walter Yonge the Manor of Catherston in Dorset with the advowson of the Chapel of St. Mary for £2600. William Ellesdon at that time also owned Newlands which had been bought by Anthony Ellesdon,his father in 1649. The marriage of William`s daughter, Mary to Richard, son of Richard, Senior sealed the union of these distinguished families in 1684. The parish records for Wootton Fitzpaine,near Catherston, show Richard born to Mr. Richard and Mary Henvill in 1685,then William in 1687, Anna in 1688, Mary in 1690 and Margaret in 1693. When Richard Henvill, Senior died in 1692 he left his son, Richard, the Catherston estate, where he was living at the time and also Lower Looke and many other properties.

The photograph shows Catherston Manor with its Tudor tower porch before it was remodelled by the Bullens at the end of the 19th century. The plan above is from the Tithe Map and shows it as two separate buildings that were later joined by a middle section. It is believed that the Henville family, who owned the manor from 1669 until 1783, altered the house, adding an impressive panelled staircase in the early 18th century. In 1689 at the Lyme Regis Election of the 29 votes for Sir Wm. Drake, five were foreign Freemen who were Francis Alford, William Bragge, John Fry, Antony Floyer, and Richard Henvill of Catherston.

By 1700 Richard and his family had returned back to Looke, near Abbotsbury from Catherston after the death of his father and built a fine Queen Anne mansion, which still stands. Their initials with a date of 1700 are carved on a stone above the doorway. Richard went on to be High Sherriff of Dorset in 1723 and lived on until 1732, aged 68. He was buried in Litton Cheney Church. There is no record as yet of Mary Henvills (nee` Ellesdons), his wife`s death or burial place, though it may well have been the same as her husbands.

The photograph shown here is of the house today from the side with the decorative stonework above the entrance. It was difficult to get to the entrance, but a similar stone shown here with Richard Henvill`s initials was above the mill house nearby. Richard and Mary Henvill were to have three successful sons, Richard, Charles and Robert, who each took different paths in life. Charles inherited the Looke Estate and the Manor of Catherston, where he lived. The Looke mansion and estate was sold by the family after the father died in 1732 and no doubt Charles moved to Catherston. He is shown to marry Elizabeth Hodder of Compton Valance in Dorset in 1739. He died in 1760 and was buried in Charmouth and his wife 10 years later. Her Will shows her living at the Manor House in Catherston at the time, amongst the items she bequeaths is a silver tankard marked with "Mr. Ellesdons Arms". They do not appear to have any children on their deaths and their estate at Catherston and also that at Yandover, near Bridport goes to his niece Benedicta Durston (nee`Henvill).

.jpg)

When Anthony Ellesdon died in 1737 at the fine age of 79 he had outlived his wife Anne, who had died in 1717 and had no children to leave his estate to. It may well have gone to his nephew Thomas Ellesdon, son of his brother, Captain John and his wife Honour who lived at Lydd in Kent. He had moved to Charmouth in 1726 on marrying Mary Henvill, a widow, who lived in the village and was related to his aunt Mary who was married to Richard Henvill. He had inherited a large estate and wealth on the death of his mother in 1725. Unfortunately, his wife died two years after their marriage and he in 1731. His Will and list of belongings, shown here which is quite substantial was left to his uncle, Anthony Ellesdon.

Charmouth possessed 3 important Inns, these were the 3 Crowns (later the Coach and Horses), The George and The Fountain (later Charmouth House) which all benefited from the regular coaches that passed through the village on their way to Dorchester and Exeter. Improvements were made both to their service and the roads in the mid-18th century and a newspaper report of April 9th, 1739 reads as follows:

"Our townsmen beheld by only going to Charmouth, the wonder of the day, better known as "The Exeter Flying Stage Coach" which reached Dorchester from London in two days and reached Exeter in three days. The lofty Stonebarrow Hill had to be ascended from Morcombelake and the descent - a perilous one - to be made by the main road, better called narrow lane, beyond the eastern brook by Charmouth, since abandoned for one further inland, and recently for one still further inland, by which the hill from Morcombelake is altogether avoided."

Richard Henvill,Charmouth`s absentee Lord, described himself as a Bristol Merchant on the marble memorial he had erected to his Uncle Anthony in Charmouth Church, although it was more unsavoury than this. The first record we have of Richard in Bristol is in 1709 when he is the Agent for the “Henvill Galley” which sailed between Guinea, Jamaica and England with its cargo of slaves.

The engraving shown here by the Bristol artist,Nicholas Pocock was one of many he made of the ships which travelled to Africa and the West Indies that include images of the people who were enslaved as human cargo in the 'triangular' trade between West Africa, the West Indies and America, and the UK. The Jason is depicted at anchor, with what may be pilot and crew approaching in boats from the left and right. The ship's crew is shown preparing the ship to set sail for Africa, as the pilot and commander arrive in small boats. This highlights the trade Richard Henvill was in with yearly trips to either Barbados, Montserrat and Jamaica.

In 1723 he initiated his first trip on the 80 ton Brigantine “Oldbury” to St. Kitts in the Leeward island. Here the slaves were consigned to Henvill & Webb for sale. The Henvill referred to is his brother Robert who was now living on the Island and was described as a Slave Factor. There followed a number of trips both to his brother and other Ports in the West Indies. In 1724 “The Fame” sailed from Guinea with 134 slaves which were then consigned to Robert Henvill who was also named as the vessel's owner at that time. It is interesting to see that one of his ships was named after his wife and daughter “Benedicta” in 1728.

In 1744 Richard gave evidence to the Lords Commissioners for Trade and Plantations that Bristol sent out 40 slave ships per year each with goods on board worth £4000. Richard Henvill had a fine house in Queens Square in Bristol, where the rich and wealthy lived, which still stands today. His obituary in 1756, records that he was an eminent Merchant of the city and had suffered from Palsy for many years.

Another brother Robert Henvill lived at the time in St. Kitts in the West Indies. In order to receive slaves, those in the Caribbean would trade cash crops such as sugar, rum, wood and molasses in return for slaves. This became the Triangular Trade. Slaves were captured and brought to the coast of Africa, where they were traded to Europeans in return for arms and liquor. The slaves were then shipped to the Caribbean through the infamous Middle Passage. On average, 12% of the slaves never made it across the Atlantic.

Robert Henvill was one of the earliest British plantation owners from the West Country. He was to succeed in his chosen occupation and married the daughter of Sir Constantine Phipps, Esq. They were to have two sons, both of whom remained on the Island. Richard married Ann Gateward and was described as a Merchant. His brother, Robert married Sarah Elmes and became a Barrister in Law.

Sugarcane was the most prosperous crop grown in the Caribbean area. The following illustrations show the slaves that were employed on the Plantations.

.jpg)

Using sugar mills, sugarcane was pressed with heavy rollers to squeeze out all of the juice. Then the juice was boiled and clarified and placed into forms. While in these forms, the liquid crystallized into sugar. The by-product was drained from the crystals and used to make molasses and rum. These two products were also exported in return for other goods, such as slaves

Richard Henvill Esq. is shown on the 1754 Map of St. Kitts with his Plantation in the Parish of St. Pauls. Notice the distinctive Windmill used as a source of power for the sugar refinery. He held a high place in society and a letter from James Verchild, esquire, Commander in Chief of the Leeward Islands, to the Board, dated November 19th, 1766, shows him recommended for the Council for the Island of St. Christopher's.

Richard Henvill was to be Lord of the Manor of Charmouth for nearly 20 years, but probably never lived here. He left his large estate to his daughter, who was just 29 at the time and unmarried. Later in 1760 she was also left Catherston on the death of her uncle Charles Henville. in 1763 she married the Rev. Joseph Durston, Rector of Compton Greenfield, near Bristol. Sadly, if one looks at the fine memorial to him, which bears a striking resemblance to that paid for by her father in Charmouth, he was to die just 7 years after they were married and less than a year in his new position. On his death she moved to Charmouth, living at the Manor and her name appears on deeds at the time relating to her position as Llady of the Manor. She herself died in 1781 and was buried next to her husband in St. Mary Magdalene Church at Berrow, near Burnham on sea.

She was no doubt living in the village either at Charmouth or Catherston Manor as her signature appears on documents of the time, some of which are shown here. In 1771 she leased the building that was later known as the “Wander Inn” on the Street in Charmouth to Thomas Rickard, her Steward. He appears later in the Quarter sessions when “Benedicta Durston, Lady of the Manor of Charmouth in the County of Dorset did and by her deputation in the year 1770 nominate constitute and appoint Thomas Rickard (her Bailiff and Agent) to be her gamekeeper of within the said Manors of Charmouth, Catherston and Newlands with full power and License and authority to kill game in the said Manors for her sole use”.

At a Court Leet held in 1770,in consideration of a good road being made in the lane leading to the sea (Lower Sea Lane) at the cost and expense of the Parishioners, she renounced all her rights. At another Court Leet in the same year it was stated that there ought to be a pair of Stocks erected within the manor at the expense of the Lady of the Manor.

.jpg)

We have Francis Henvill to thank for commissioning whilst he was her, the famous cartographer, James Upjohn of Shaftesbury, to produce a detailed map of Charmouth and Newlands. It would be wonderful to locate where it is today as it would provide a window on to the village in that year. The index to the map was found by the historian, Reginald Pavey and he wrote out a copy of it which is very useful in tracing back the history of buildings and fields in the village. The map shown here is the later Tithe Map of 1841 which provides a taste of how it may have looked. On the same slide is an abstract from Benedicta’s Will leaving Charmouth to her cousin and his appearance on the grand jury of St. Kitts in 1786.

There is a reference to Francis, owner of Ottleys Estate in 1822 as a widow marrying Sarah Ann Kelly, spinster, eldest daughter of Mrs. Mary Kelly of Basseterre, widow, of the late David Kelly, Esq., Attorney-at-Law. The marriage obviously did not last long as three years later he was living at Sandy Point married to Mary Michael, only daughter of Robert Spence, Esq.

The Ottley Plantation House where Francis once lived is now a luxury Hotel as seen on this photograph, a fine departure from its original source of income based on slavery.

Rev. John Audain

.jpg)

The Rev. John Audain was to appear annually in the Poor Rates, Land Tax and other records for Charmouth from 1783 until 1825. He was to receive a Stipend every year as Rector for over 40 years, whilst his Curate, Brian Coombe carried out all his religious duties. Although he was here for 4 years, he returned back to the West Indies and never returned. He was to lead a debauched life there and was known as the “Pirate Parson”. Thanks to the internet and a number of books and articles, it has been possible to piece together his life story and separate fact from fiction as far as possible. It makes for a fascinating story and shows him as a smuggler, slave trader, privateer, bigamist as well as a Parson, often at the same time.

When Rev. William Coombe died in 1783 he had held the position of Rector for over 35 years.His family were rich Clothiers from Shepton Mallet and their memorial in the church of St Paul and St Peters is shown here. His obituary records that “he was assessor for the land tax, house tax, and highways, register and entry clerk and keeper of all the parish rates, papers etc. Belonging to the said parish, and a commissioner of the turnpikes. Besides those numerous offices, he also was frequently overseer. He died rich, and has left one son, the Rev. Mr Brian Combe, fellow of Oriel College at Oxford, who it is thought would succeed his father in or most of the above offices, if he should be presented to the Rectory aforesaid”. His son would have been just 25 at that time and it was the same year as he was ordained, ready for a senior position in the Church. One would have thought that the fact he was born in the village and was well respected that the position was his. Unfortunately for him and the village it was not to be. For at that time the Patron of the village could choose whom he wished.

.jpg)

That position was held by Francis Phipps Henvill who was a distant cousin of Benedicta Durston (nee` Henvill) who had died just 2 years before leaving him the Manor of Charmouth. He and his family owned sugar plantations in the West Indies and were absentee landlords. This did not stop him from choosing his cousin Rev. John Audain to fill the position of Rector in Charmouth and Brian Coombe to be Curate. Benedicta Durston also owned Catherston Manor and left that to another cousin, Robert Elmes Henvill. It was he who gave the position of Rector of Catherston to Brian Coombe. The family Tree for the Audains shows their descent from a branch of the Henvill and Ellesdon families and how John Audain was cousin to Francis Phipps Henvill.

The Reverend John Audain`s story begins on the island of St. Kitts in the West Indies, where he was born in 1755 to Dr. John and Mary Audain. His father is described as a Surgeon in documents from that time. His mother was born Mary, daughter of Robert Henvill in 1726 at Sandy Point on the island of St. Kitts in 1726. It is her uncle, Richard Ellesdon Henvill, who is the Lord of the Manor of Charmouth and Catherston from 1732 until 1756, when it is inherited by his daughter Benedicta Henvill. On her death in 1781 she leaves her Estate to her cousin, Francis Phipps Henvill, nephew of Dr. John and Mary Audain. Both families own extensive Sugar plantations on the island and are amongst the elite.

A detailed map of St. Kitts produced in 1753 shows how extensively the island was covered with Sugar Plantations and refineries, almost all controlled by wealthy British families, who were to make and in time lose their fortunes there. Their names are recorded on the sides of the map.

Dr. John Audain, father of Rev. John Audain is shown to have one near Sandy Point in that year. He was to purchase another plantation at St. Paul’s, Capisterre with 79 acres and 56 negroes from William Woodley in 1762. Sadly, he was to die the following year, leaving a wife with her 8-year-old son, John to look after. Both his siblings had died young and as the survivor he must have been cherished by his mother, Mary.

On the Key to the list of subscribers it is interesting to see John Audain for the Heirs of Colonel Henville Deceased. This was Robert Henvill, father of Mary Henvill who had married John. He died in 1752 and his wife Susannah, daughter of Francis Phipps in 1754. In the right panel are Francis Phipps Esq and also the Payne family, who John Audain was to marry into.

It is known that John Audain was initially a Midshipman, and no doubt after his schooling took up this life at sea, after four-year training. The life of an officer did not suit him, and he abandoned it to follow his religious leanings for a training in the church. It is during this time that at the age of just 21 that he marries Ann Willett Payne, born in the same year on the island of St. Kitts. They may well have been childhood sweethearts as both families had Sugar plantations at Sandy Point as seen on the 1753 Map of the island.Her parents were Abraham Payne and Ann Willett. They were members ofone of the wealthiest families in St. Kitts owning a number of sugar plantations.John and Ann are shown to have a son, John Willett Audain born in 1777.

Their lives were to change in 1783 when shortly after he was ordained the opportunity arose to take up the post of Rector of the village of Charmouth on the death of Rev. William Coombes. The fortunes of the sugar plantations had been jeopardised by both the war with America and France, with the loss of those markets and many were in dire financial difficulties. This must well have been the case with Francis Phipps Henvill, the cousin of John, who in that year owned considerable property in both Charmouth and Catherston.

He is known to have come to England with his cousin John Audain and his family. As Lord of the Manor and Patron of the church he was able to choose who he wanted as the new Rector. He was to overlook, Brian, son of William Coombe and choose his newly ordained cousin, Rev. John Audain for the position.

Benedicta Durston, the heiress of the Henvill Estates had left Charmouth to her cousin, Francis and Catherston to another cousin, Robert Elmer Henvill, barrister of St. Kitts. It was he that chose Rev. Brian Coombes as Rector of Catherston, on the death of his father. Unfortunately, he did not see the year out and left the Manor to Francis. This created the strange situation, whereby Brian Coombe was Rector of Catherston, but only Curate at Charmouth.

On the death of his father, Brian Coombe was to receive a considerable fortune and a number of properties.In 1788 he purchased Backlands and Stone Barrow Farm from the Henvill Estate. He lived with his mother where Devonsedge is today.The photograph shows it as the white building with a blind behind the Cart Horse. It was destroyed with its neighbours in a devastating fire in 1895. Brian`s Aunt, Mary Coffin lived in the adjoining house on the right, which is now where Lansdowne House stands. He never married and left his large estate to his five nieces. He was hard working and spent his life in the village assisting those around him.

John Audain right from the beginning of his term left the running of the church to his very capable Curate. He appears just the once as Rector in the Churchwarden accounts in the year 1784 shown here.

His name is also lacking in the list of marriages, where it can be seen that Brian continued officiating with these after his father had died in August 1783.

There is one interesting record in 1784 which gives us an insight into his wife’s family. For in that year her brother, the Rev. Ralph Willett Payne died intestate, leaving her his estate. He died young and must have been close to John and his wife as both originated from St. Kitts and were clergymen. Ralph Payne was buried at Canford Church, where his cousin Ralph Willet was patron and commisoned this engraving.

Ralph Willett, had made his fortune in the family Sugar plantations and had built the magnificent Merley House at Wimborne in Dorset out of hia profits. This is where his cousin was staying at the time of his death. When Ralph Willett died in 1790, he left £50 annually to his cousin, Ann, who was the wife of Rev. John Audain.

On scouring the internet, we found a strange reference to Rev. John Audain being a witness to a crime at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1787. It was very helpful in providing further information about why and when he returned to the West Indies. It would seem that he was attending a performance at the Theatre when a George Barrington attempted to steal a purse containing 23 guineas from a gentleman who went by the name of Haviland Le Mesurier. John was quick off the mark and held him whilst the culprit shouted out "Gentlemen don’t expose me". He was then apprehended and John with Haviland swore an oath the following day, which is shown here about the incident. The Pickpocket escaped and then followed a gap of two years before the case was brought to the Old Bailey in London. In between time the key witness our John Audain had returned back to the West Indies

The Court was told that: “I should have had to produce to you a witness that you would have thought very material; I state this, because I think it is incumbent on the prosecutor in every case to remove all doubt, and to produce every person to the Jury, that in his apprehension can assist in such removal. Gentlemen, the person I allude to is Mr. Audain, who you will find would certainly have been that material witness; that gentleman has an estate in the West Indies, he has been called and has remained there for two years; therefore it would have been impossible to have had the trial put off on his account; it would have been improper, and the Court would not have suffered it”.

As a result of the loss of the prosecution`s key witness, The Jury gave a verdict of not guilty and George Barrington, a famous Pickpocket was again free to pursue his life of crime until finally being convicted and transported to Australia, where surprisingly he made a fortune and was well regarded. It is interesting to read that Rev. John Audain had urgent reason to return to his Sugar Planation, which were in serious decline at the time that he went.

After the sale of the Manor of Charmouth to James Warden by his cousin in 1788, John Audain had the retired Lieutenant James Warden as his Patron. He was a difficult character and was very argumentative, even taking the Curate, Rev Brian Coombe to court, accusing him and others of taking stones from his beach. He ultimately ended up in a quarrel over a barking dog with a neighbour and died in a duel in 1792. His impressive tomb is still to be seen by the entrance to the church.

There is another insight into his nature given by George Roberts in his “History of Lyme Regis and Charmouth”, published soon after he left. He relates the following anecdote

“He fought a battle at Lyme Regis with an Irish chaise driver and preached with his usual energy. His preaching carried everyone with him: his fighting was good and manly, but not so successful, for the knight of the whip eventually beat him”.

.jpg)

His wife, Ann and her son, aged 10 by then, did not return and she was to move to Bristol, and John Willett to take up a successful career in the Army. She never remarried and continued to think of herself as still married to him. Her gravestone refers to her being the wife of Rev. John Audain, Rector of Charmouth, when she died at Corsham in 1833.

Initially John took up the post of Curate at St. Thomas Church, St. Kitts, in October 1787, although their Parish Records show that he resigned in August the following year. This was the family church for both his and relations with a number of burials for them recorded there, including his father and the Henvills.

The next part of Rev. John Audain`s life is mainly revealed in a chapter in the book “Six Months in the West Indies in the year 1825” by Henry Coleridge, nephew of the famous Poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He provides a number of fascinating anecdotes given to him about the Parson. It is very florid and we have attempted with contemporary facts and reports to make sense of it.

He describes how he built himself a schooner and fitted it out and carried out raids on the French,to his own satisfaction and profit. After resigning his post as Curate in 1788 there appears to be a gap before he takes on his next position as Rector and during this time Coleridge tells us the story of how he was in “Basseterre in St. Kitt's surrounded by negros, to whom he was distributing plantains, yams, potatoes and other eatables, and holding private talk with them all by turns. Having caught my friend's eye, he came up to him and said, " I am going to smuggle all these rascals this evening to Guadaloupe." He did so in his schooner but remained himself on shore. A privateer of Nevis captured the smuggler before she could get to her market. Audain became furious, went himself to Nevis, and challenged the owner of the privateer to fight. The challenge was not accepted, and Audain immediately posted the name of the recusant, as that of a scoundrel, on the wall of the Court House. He himself for two days kept watch upon the platform with a sword by his side and four pistols stuck in his belt, to see if any one dared to touch the shields. Audain fitted out another schooner and cruised in her himself. But fate was too heavy for him, though he struggled against it like a man.

.jpg)

After a gap he returned to his duties as a Clergyman by taking on the position of Rector of Roseau and St. Georges, in Dominica. A position he was to hold according to their records from 1802 until 1811, when he was dismissed. He was also elected the senior of the assistant justices of the Court of Common Pleas soon after he took up his new job..

He was held in high regard in the community and there is an incident in 1805 when the British troops were fighting the French on the island at Rouseau. It was reported that "A company, under Captain Woolesly, were detached to guard a pass on the hill, and to give timely notice of the approach of the enemy on that side. At the same time two six-pounder Guns were brought up to the gate by the great exertions of the Rev. John Audain, and some other spirited individuals, with a party of sailors and negroes.

Later in 1805 as Rector of St Georges, Roseau, shown above, he writes that "I can furnish no return of marriages because a very few even of the free coloured people marry and not one slave since I have been. Why they do not, I readily conceive, particularly the Slaves. Their owners do not exhort them to it, and they show no disposition themselves to alter that mode of cohabitation which they are accustomed to".

Coleridge writes of him that "Audain, though occasionally non-resident for the episodes of privateering continued as the Minister of Roseau. He was a singularly eloquent preacher in the pathetic and cursory style, and he rarely failed to draw down tears upon the cheeks of most of those who heard him. His manners were fine and gentle, and his appearance even venerable. He was hospitable to the rich and gave alms to the poor".

There is sighting of him in 1808 In Georgetown, United States, where he put up at the Union Hotel, “where, he charmed all the boarders with his wit and pleasantry.” We recollect when here that he had twelve very pretty little ivory apostles, which he wished to 'sell; and we believe offered them at the [Catholic] college, but with what success, we never learned.”

Coleridge goes on to describe "how he once broke off' the service on a Sunday, unable to repress the emotions of his triumph on seeing the vessel of his faith sail into the bay with a dismasted barque laden with sugar, rum and other Gallic vanities from Martinique".

Coleridge writes that his friend Mr Oxley had witnessed that “Audain was preaching one afternoon in a seaside church during a heavy south west gale, when all on a sudden his audience began to move, take down their hats, and press towards the door. The vicar, having the advantage of pulpit eminence and long experience, immediately perceived the cause, and, animated with a just indignation at their conduct, ordered them, as they valued their souls' welfare, to remain quiet till the end of the sermon. The good man in his eagerness to restrain them even left the pulpit, and, like Aaron, ran into the midst of the congregation rebuking and exhorting them, till he reached the porch ; when, tucking up his gown under his arm, he shouted out, " Now, my boys, let us start fair !" and immediately scampered off, with his flock at his heels, to administer Cornish relief to a distressed merchantman”. In 1811, he was again suspended from his living in Tortola because of an absence of some years without having left a curate to officiate and not only engaging in Commerce, but actually commanding Privateers."

Coleridge writes that "After his time in Tortola he took up as an honest trader and to St. Domingo, now Haiti with a cargo of corn, sold it well and lived on the island. He then quarrelled with two black general officers, challenged them and shot them both severely. Henry Christophe, the native ruler, shown above at that time sent for him, and told him that, if the men recovered, it was well, but that, if either of them died, he would hang him on the Tamarind tree before his own door. Audain thought the men would die and escaped from the Tamarind tree by night in an open boat".

After his escape he recommenced as a clergyman, this time on the little island of St. Eustatius, shown here, 3 miles to the north of St. Kitts, which was originally owned by England and later purchased by Holland.There were many religions, but no priest, in the island when Audain made his appearance there. Audain offered to minister to all the sects respectively.It was reported that "In the morning he celebrated mass in French,then read the liturgy of the Church of England, in the afternoon held the Dutch service, and at nightfall, chanted to the Methodists".

Major Samuel Shaw writes in his Jounal an incident on the island when "after returning from our ride, we breakfasted with Mr. and Mrs. Haffey; and our friend's politeness carried him so far as to propose attending us to the English church; an offer we the more readily embraced, from being acquainted with the parson, Mr. Audain, a gentleman of good sense and engaging manners, and who did not disappoint our expectations of him in his sacred character".

It was whilst here that he met a rich Dutch widow and married her despite still being married to his wife, by then living in Bristol. To make certain that all was correct, the bridegroom himself performed the ceremony.

There is another insight into his character when in 1814, Count Charles Roehenstart writes " that he had arranged to have a sight draft sent for him by Rev. John Audain, Rector of Charmouth to an American agent, Henry Cruger. The draft was for $500. Either it did not arrive or was unpaid for lack of funds in the Audain account. This failure to pay was unknown to him for some years, and he regarded the failure to pay as the fault of Audain, being deceived in a most shameful manner by him". It is interesting that Audain, still refered to himself as the Rector of Charmouth, which he indeed was in absence.

Coleridge writes that “Audain has fought thirteen duels and was a good boxer. Once upon a time, he fired twice without hitting; upon which he threw down the pistol on the ground, and said sternly to his second, " Take care that does not happen again!" supposing his pistol had not been charged with ball. A delay occurred in reloading for the third time, upon which Audain went up to his antagonist, squared his body, and saying, " Something between, something between, good sir !" knocked him down with a flush hit on the nose”.

In summing up at the end of his chapter on Audain, Coleridge records that"he had wholly reformed his manners. He loved his Dutch wife and says his prayers so loud at night as to disturb his neighbours. His English wife sends him a Christmas box annually. He was a man of infinite talent and had seen the world".

He did indeed lead a full and colourful life and was to die in 1825, aged 70 and was buried on the island of St. Eustatius. The wife he had left in England died in 1833 aged 78 in the village of Corsham, near Bath. Her grave is seen here at the front of the photograph in which she is recorded as being the wife of Rev. John Audain of Charmouth. Tragically their son Colonel John was buried by the side of her after passing away just a few days later. His own son, Willett Payne Audain also went on to be Colonel in the army and we are later told that "he resided at Fitzroy- avenue, Belfast and was the surviving representative of this historic family. He had in his possession several valuable memoirs, besides a rare collection of antique sculpture of great value, which his grandfather, the Rev. Dr. John Audain, purchased from one of Napoleon's generals, who had taken it out of the pope's palace at Rome".

The Reverend Brian Coombes held the position of Curate in Charmouth until his death in 1818. He never married and his considerable estate was inherited by his 6 nieces.

As a postscript

there is a newspaper report in the Dorset County Chronicle and Somersetshire Gazette in 1826, a year after his death “respecting Mr. Audain, the Rector of Charmouth, (now resident in the West Indies) may be interesting to many of our readers. It is taken from a book published in the early part of the present year under the title of “ Six Months in the West Indies in 1825”. Mr. Audain has, we believe, for many years past been engaged in clerical and commercial pursuits in the West Indies. He is still Rector of Charmouth, but has been non resident for upwards of twenty years, and his living is now under sequestration by the authority of the Bishop of Bristol”.

The following week a disgruntled reader writes to the Editor

“Sir, - In addition to, and indeed correction of, part of the singular account given of this extraordinary gentleman in your last number, it may not be uninteresting to some of your readers to know that this Rev. Audain is no longer Rector of Charmouth, his extravagant and inconsistent conduct having deprived him of a living which he proved himself so utterly unworthy. The present Rector, the Rev. Glover, was inducted about a fortnight since, and it is saying far less than his high merits deserve, that he is in every respect the opposite of his misguided predecessor. Yours, £c., B.M.W. Charmouth November 13,1826”.