1832

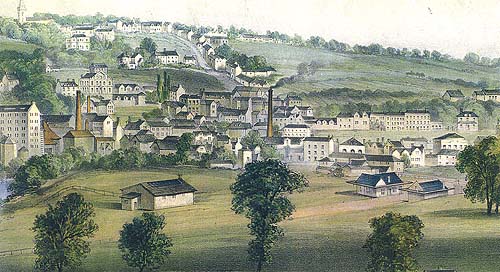

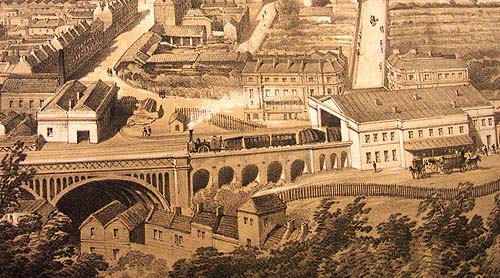

The idea of a railway link between Bristol and London was promotedin 1832

by two engineers, William Brunton and Henry Habberly Price. The route

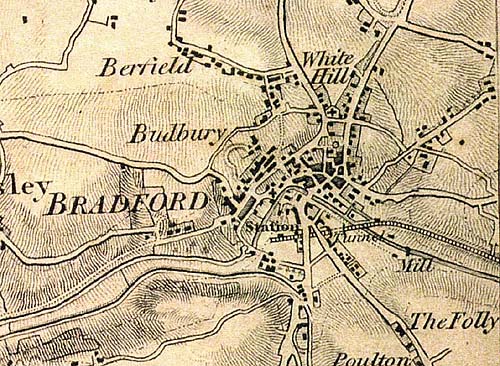

proposed was from Bristol, via Bath, Bradford and Trowbridge, then passing

near Devizes and through the Pewsey Vale to Hungerford, thence through

Newbury and Reading, Datchet, Colnbrook and Southall 'to a vacant site

within three or four hundred yards of Edgware Road, Oxford Street, and

the Paddington and City Road turnpike.This project was announced by a

circular headed 'Bristol and London Railway' and dated from 7th May 1832,

and repeated by another letter in the following month, but never materialised

due to lack of financial support.

In July 1832 the London and Southampton Railway's promoters decided to

seek powers for the Southampton line alone and to delay presenting the

Bristol Bill.

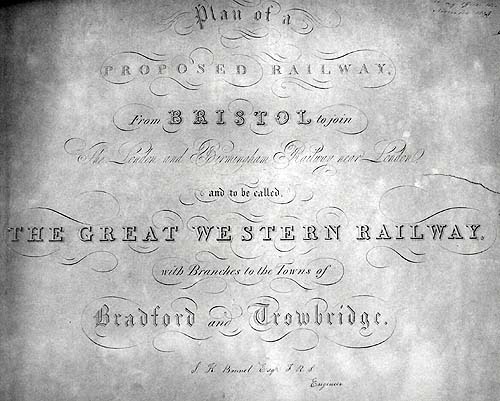

Bristol

citizens launched a separate proposal for a Great Western Railway(GWR)

linking Bristol to London. A bill for two lines at either end connected

temporarily by a canal was put forward in 1834, but was rejected by the

Lords.

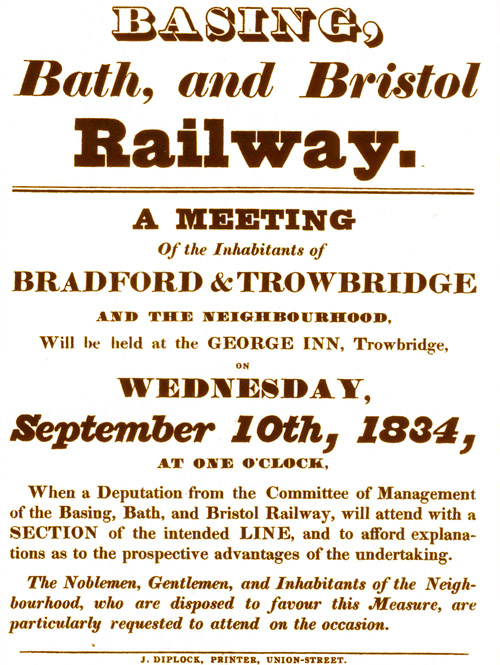

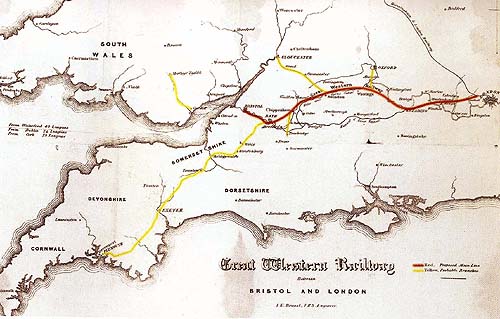

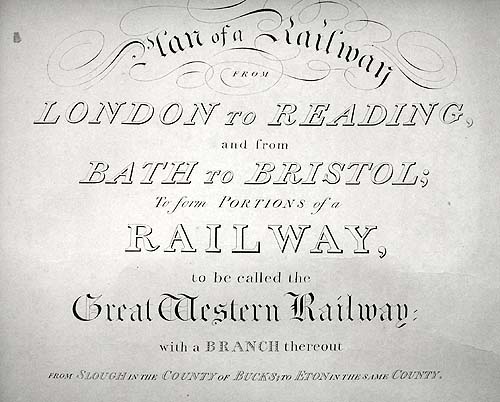

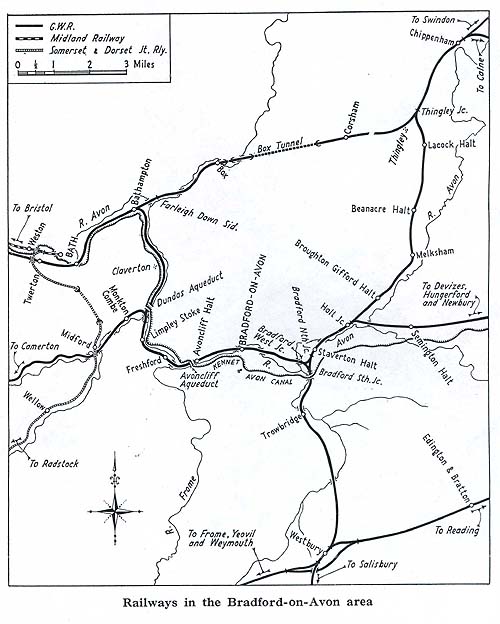

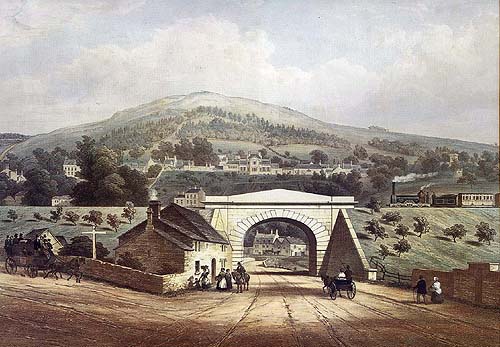

The Basing and Bath prospectus of 1835 proposed a 106 mile line via Newbury, Devizes, Trowbridge, Bradford on Avon, and Bath with a westward extension to Frome, Taunton, and eventually further west. The opposing GWR was to go through Slough, Maidenhead, Reading, Swindon, Chippenham, and Bath. The revised GWR Bill of 1835 included branches to Bradford on Avon and Chippenham. The Commons accepted it against the Basing and Bath primarily on the grounds of its easier gradients.

Meanwhile, the London & Southampton, having obtained their Act, began another attack on the Great Western by promoting a 'narrow gauge' line from Basingstoke to Bristol via Newbury, Hungerford, Devizes, Trowbridge and Bradford. There was little support for the 'narrow gauge' scheme from either Bath or Bristol, and at a public meeting held in Bath in September by the London & Southampton, Brunel successfully demolished their arguments and the resolution was carried in the favour of the GWR. The London & Southampton, although rebuffed, was not put off by this result and proceeded with their Bill for the Basingstoke, Bath & Bristol Railway. The GWR, sensing that trouble could be looming with the proposed L&S line from Basingstoke, added a forked branch from Chippenham to Bradford and Trowbridge into their new Bill.

By the end of February 1835, the GWR was able to announce to the public that the whole of the 10,000 additional shares required by Parliament for the entire railway from London to Bristol, making, with the previous 10,000, a capital of £2 million, had been subscribed and that the petition for the Bill had been

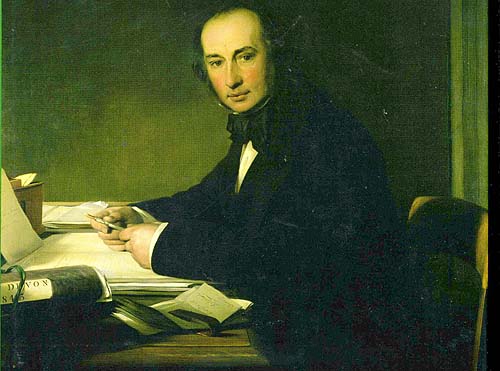

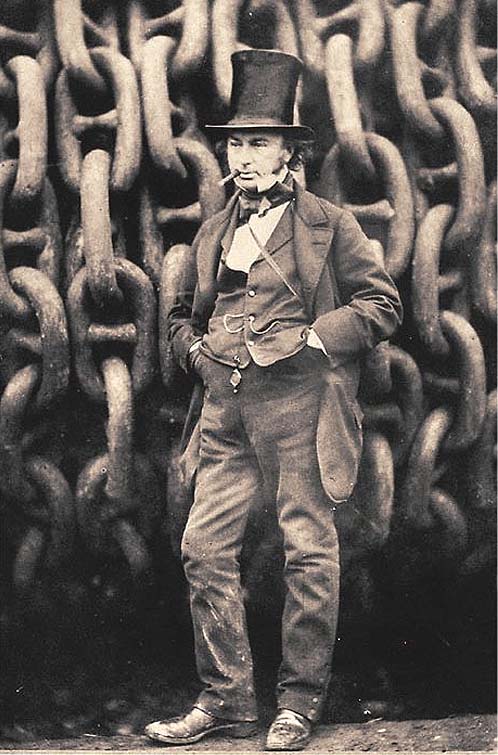

However, with railway fever still holding Bristol in its grip, and with much discussion in the press and between influential commercial groups, other persons were quick to adopt the idea. Four successful businessmen started the ball rolling in the autumn of 1832, with the result that, by the end of the year a committee of prominent merchants and others representing the five corporate bodies of Bristol -Bristol Corporation, Society of Merchant Venturers, Bristol Dock Company, Bristol Chamber of Commerce and the Bristol & Gloucestershire Railway - was appointed to investigate the practicability of a railway to London. The first meeting was held on 21st January 1833, and the committee considered the matter generally and advertised for information. During the following month the constituent public bodies, having received favourable prospects for the intended line, provided funds for a preliminary survey and estimate, and this involved the selection of an engineer. On 7th March 1833, Isambard Kingdom Brunel was appointed to this important post at the age of 27. He, in company with W. H. Townsend, a land surveyor and valuer, set about surveying the country between Bristol and London. First, they inspected the route between Bath and Reading via Bradford, Devizes, the Pewsey Vale and Newbury, in the footsteps of the previous project, then the second route, north of the Marlborough Downs, via Chippenham, Swindon, the Vale of the White Horse and the Thames Valley. This latter being the route selected.

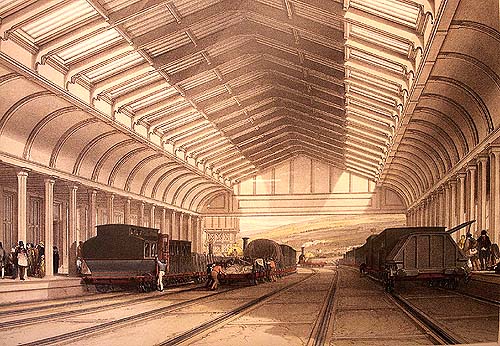

1835 The Great Western Railway was created by an Act of Parliament on the 31st August 1835 to provide a double tracked line from Bristol to London

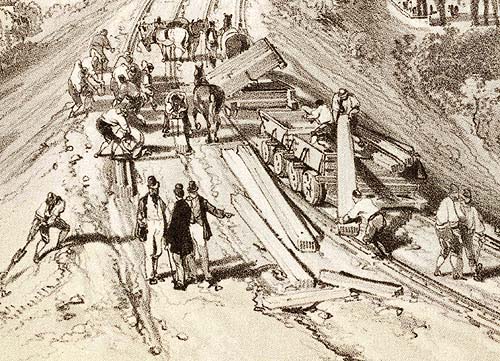

He undertook the entire supervision of the construction. Every detail of locomotion, construction and administration

was decided by him. He prepared contracts and vetted tenders, designed tracklaying tools, negotiated with landowners and trustees of charities, turnpike roads and proprietors of waterways, issued instructions to subordinates, corrected their behaviour towards landowners and contractors. While the Great Western was building he became Engineer to the Cheltenham & Great Western Union railway and the Bristol & Exeter Railway and thereby trebled his comprehensive responsibilities.

15th September Brunel announced his intention of using a wider gauge than normal ( 7 ft rather than 4ft 8 1/2 in between the rails).

1837 the Great Western also launched their first ship, appropriately named 'Great Western', as Bristol had direct access to the Atlantic and America. A few years later they produced the first completely iron steamship 'Great Britain' and her troublesome sister 'Great Eastern', all designed by Brunel

1838 The first section of twenty-four miles from Paddington to Maidenhead was completed in May 1838.

1841 Great Western Railway completed to Bristol in June . The whole route to Bridgewater was opened on 30th June. Branch to Bradford on Avon not built as insufficient money.

1844 9th

July first meeting of Wilts & Somerset Railway was held at the Baths

Arms Inn ,Horningsham,Warminster with major land owner-Walter Long as

Chairman and I.K. Brunel as Company Engineer.

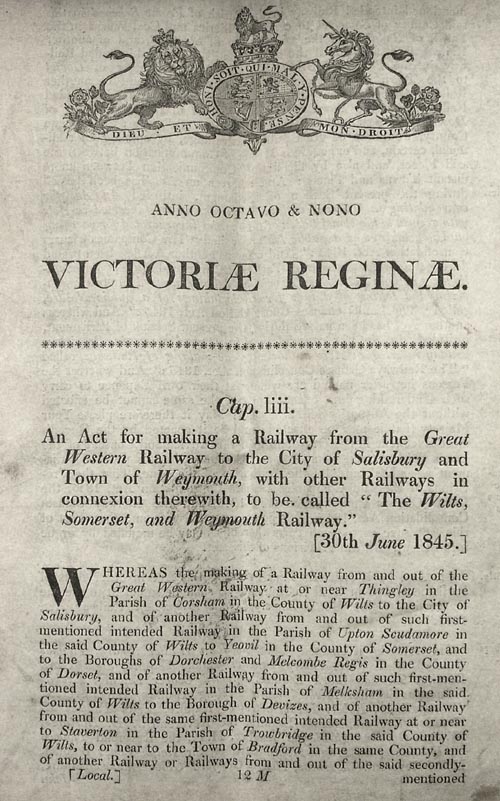

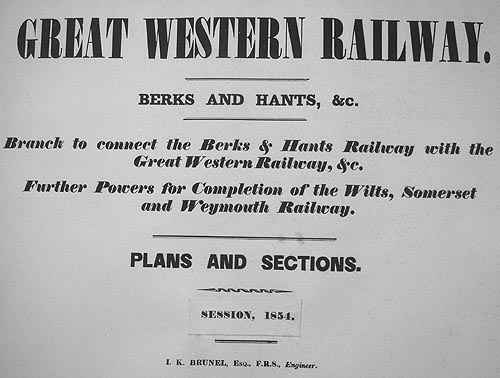

The

London & South Western Railways proposed a line from Basingstoke to

Swindon, in the heart of Great Western Railway territory. The Great Western

Railway retaliated by promoting two nominally independent companies to

extend the broad gauge, the Berks & Hants, and the Wilts, Somerset

& Weymouth, both of which obtained their Acts on 30 June , the following

year.

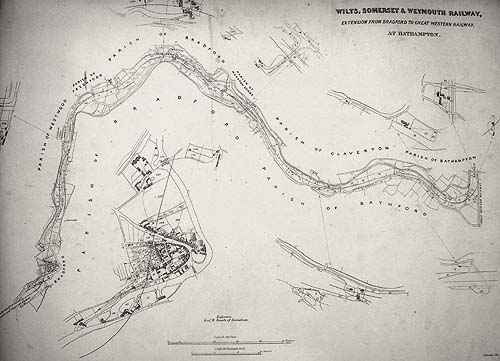

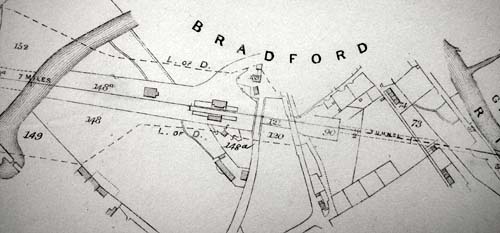

The Wilts, Somerset and Weymouth Railway Company applied to Parliament in 1846 for an Act enabling it to compulsorily purchase land for the new railway which was eventually granted upon the strict condition that the short branch from Staverton to Bradford-on-Avon should be extended through Freshford and Limpley Stoke to a junction with the main line at Bathampton in order, in the words of the Act, "to effect a better line of communication with Bath and Bristol."

3rd August Act receives Royal assent. The Great Western Railway, which was supporting the nominally independent Wilts, Somerset and Weymouth, vehemently opposed this condition but was compelled to accept it in order to get the Bill passed.

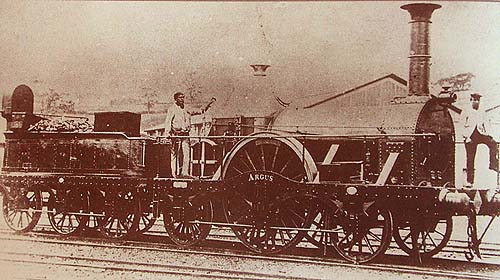

"On Saturday (2nd September) the directors, accompanied by numerous friends, made an experimental trip on the line from Thingley to Westbury, preparatory to the opening for general traffic. At twelve o'clock a special left this city, drawn by the Vulture engine, which was driven by Mr. Gooch, Superintendent of the Locomotive Department of the Great Western Railway, assisted by Mr. Brunel, Engineer. At Melksham the train was received with loud cheering from the assembled populace, flags waving and bands of music playing. At Trowbridge also there was a great assemblage of people, and salutes of cannon were fired from the iron foundry. At Westbury, the Mayor presented the directors with a congratulatory address, to which a suitable reply was returned by the Chairman of the board."

The line opened to public on 5th September. Work was finally completed at Avoncliff.

1849 proprietors of WSWR told that the depression only minimal work was being carried out mainly from the Westbury to Frome section. Finances deteriorated during the year. By December the directors had sold the company to the Great Western railway.

1850 14th march the Wilts, Somerset & Weymouth Company absorbed by Great Western Railway.

Some of the land was re-let, much of it to the previous owners and the countryside for many miles along the route was punctuated with stretches of half-completed earthworks and bridges. The branch from Staverton to Bradford was completed and Bradford station built, but the rails were not laid on this section, much to the annoyance of the local populace! On 4th June 1849 the WS&W directors were advised by the Great Western to suspend all the workings of the line except the section from Westbury to Frome. In a report to the shareholders presented with the half-yearly accounts in January 1850, the GWR advised that the lines should not be extended for the present beyond Frome and Warminster.

Although the WS&W was a nominally independent concern it had always in reality been a creature of the GWR, the hope being entertained that a seemingly local company would make better progress with raising subscriptions. By now it was obvious that this was untrue, so the pretence was ended by the GWR taking over the WS&W and its unfinished line of railway on 14th March 1850. The GWR gave the shareholders of the now defunct company 4% guaranteed stock in lieu of their ordinary shares - a purely paper transaction since the GWR had, from the line's inception, guaranteed 4% on the capital and invested £545,000 in the project. Transfer of the former company to the GWR was confirmed by Parliament on 3rd July 1851, and the erstwhile Wilts, Somerset & Weymouth Company was dissolved 1851 the transfer to GWR was legalised.

The people of Bradford-on-Avon, who had seen their station completed in every detail apart from the laying of track, had good reason to be furious that no attempt was made to finish their part of the line. Indeed, there was a general disenchantment with the GWR throughout the district, and many towns -including Devizes, which was pressing for the completion of its branch, served Bills of Mandamus upon the GWR which culminated in a lawsuit at Somerset Assizes in the Michaelmas Term of 1852; a writ against the railway company being sought to compel them to complete and open the whole system. This action met with only limited success. The GWR, being able to prove that their financial position was far from strong, was successful in defeating many of the lawsuits, but Mandamus was made absolute for the Avon Valley section through Bradford-on-Avon to Bathampton. The GWR lodged an appeal against the order, but it was dismissed, with the Exchequer Chamber deciding that under the terms of the 1845 Act, the Company could be compelled to make the branch.

With land being purchased beyond Frome for the continuation of the line, and the company entering negotiations with various local bodies in order to obtain the capital for finishing the railway, the GWR, under an Act of 1852 made another attempt to stimulate local interest by floating a separate company under the title Trome, Yeovil & Weymouth Railway'. The Act contained a clause that the agreement with the GWR should be void unless the the whole capital was subscribed within three months, but this was not

1853 Proceedings were taken for writs of mandamus to compel the completion of all the lines. Naturally the GWR was made scapegoat for the district's economic troubles, but the Company proved that times were hard for it too, and was successful in its defence - except for the Bradford to Bathampton section. Mandamus for this was made absolute by the Queen's Bench in Michaelmas Term 1853 after a much publicized trial at Somerset Assizes, and an appeal was rejected.

1855 Wiltshire Record office has a document relating to the sale by John William Yerbury of land at Belcombe to the Great Western Railway ( 686:22).In this year GWR had to raise more capital, to the sum of £1,325,000, to complete various works including Wilts, Somerset & Weymouth. In the shareholdsers report of 1856 it was revealed that £1,433,000 had already been spent on WS&W. At that time only 311/2 miles of the project were open to traffic.

1856 By 1856, the GWR had already spent £1,433,000 on the Wilts, Somerset & Weymouth; and the opening of the rest of the system, through thinly-peopled country, was expected to bring an operating loss. This was but one factor then contributing to the GWR'S difficulties and dissension on the Board.

Colonel Wynne made an inspection on behalf of the Board of Trade on 17 January 1856 and believed another three to four months was required for completion. The work which ruled the opening, was the tunnel under the Kennet & Avon Canal at Dundas Aqueduct. It had to be cut through material of a treacherous nature and the side walls were built in lengths not exceeding 10ft and each had to be built in a pit, the sides of which had to be shored up closely all round. It was impossible to drain the canal as it had to be kept open to traffic. 1857 Colonel Yolland inspected the Yeovil-Weymouth line on 15 January .

On July 21sy 1856 the Wiltshire Times reports:

An accident occurred here on Wednesday morning last, resulting in fearful consequence by the falling of a wall near the line of railway, which fell on two workmen, one of whom is dead and the other is not expected to survive.

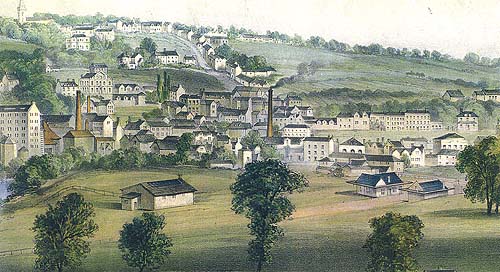

Opening of the railway to Bath

On Monday last the line between Trowbridge and Bath via Bradford was opened for traffic. The first train arrived here soon after 7.00 am and 10 trains are registered to run, viz 5 up and 5 down. Considerable excitement prevailed throughout the day, on the arrival of each train the railway station was besieged by hundreds of eager spectators. The celebrated Bradford brass band played lively airs at intervals during the day, and as often as might be heard the sound of the merry church bells. A good dinner was provided in the evening by Mr J,C. Neale of the Swan Hotel. We learn that the inhabitants of the town are not contented with the list of fares laid down by railway company; for a return ticket from Bradford to Bath a distance of 9 miles, a fare of 3/3d is demanded, whereas from Trowbridge to Frome, a similar distance, the price is only 1/6d.

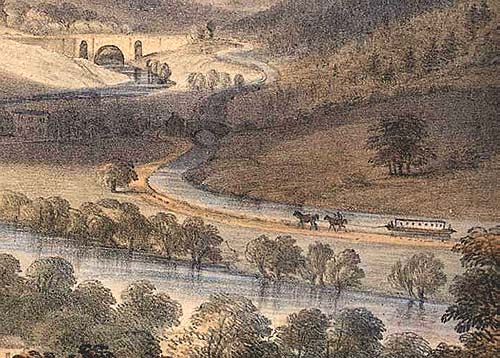

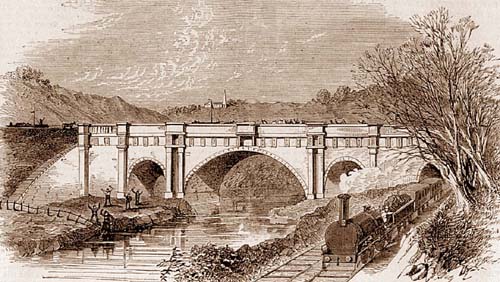

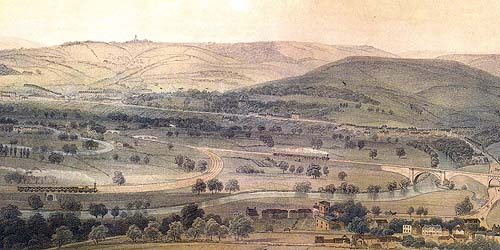

The line curves away from the main about on mile from Trowbridge station through Bradford, Avoncliff, Freshford, Limpley Stoke to the junction at Bathampton where it joins the GWR to Bath etc., passing 3 times under the Kennet and Avon Canal and 6 bridges by extensive viaducts over the river Avon.

On June 27 1857 The Wiltshire Times reports:

Bradford.

On Monday 22nd this unusually quiet train was greatly enlivened by an excursion train which stopped at the Bradford station on its way to Weymouth. Here it was joined by the brass band belonging to the town, to whom great credit is due to for the very praise worthy way in which they enlivened the pleasure of the day. The weather was remarkably favourable but a goodly number of passenger (150-200). Found difficulty in obtaining seats and it would have been easier if rail carriages had been awaiting the train, and it would have been given greater satisfaction.

2nd Class single 6d. return 9d.

3rd Class 3 1/2d.

Trowbridge-Bath was (in order as above) 2s. 9d. 4s. 1s 10d. 2s. 9d 1s.

On July 25 1857

Excursion Train (Trowbridge)

Yesterday morning a monster train from Bristol, Bath and Bradford passed our station on its way to Salisbury. It consisted of about 30 carriages, propelled with two powerful engines. The train was a very heavy one and must have conveyed about 2,000 persons. Our neighbours at Bradford a short time ago expressed themselves to be annoyed with the accommodation. They received on an excursion to Weymouth on this occasion they have been preferred. However, many persons from Trowbridge we believe availed them selves of the privilege by obtaining tickets at Bradford.

The initial service of five trains per day each way was not generous, but no doubt adequate for the available traffic. In any case, the long stretches of single track, coupled to the heavy gradients on the southern section, made anything more ambitious impossible. The last section to be opened was, ironically, that for which the Assize Court had issued a writ of Mandamus back in 1852, namely the 9 1/2 mile Avon Valley line from Bradford Junction (north of Trowbridge) to Bathampton which opened on 2nd February 1857. The long suffering residents of Bradford-on-Avon, who had been waiting for over seven years for rails to reach their completed station, received some reward for their patience in the form of a free excursion train to Weymouth. Having regard to the time of year, most of those who availed themselves of this offer probably did so for the novelty of the journey rather than the appeal of visiting a cold seaside town out of season!

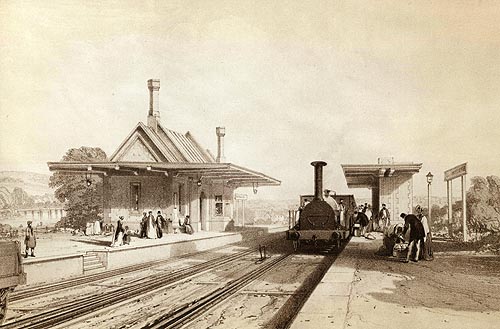

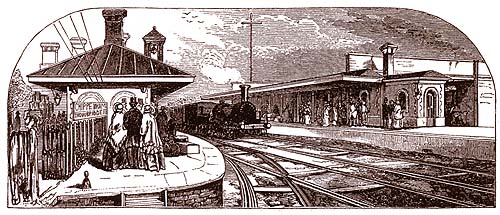

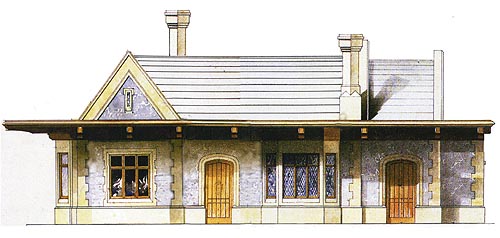

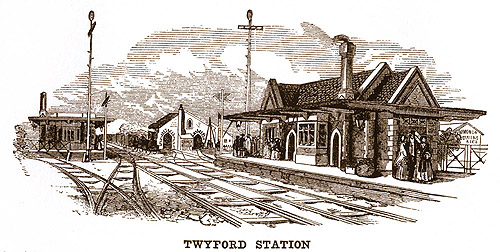

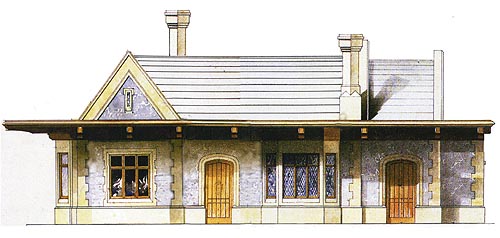

In recent years the piecemeal demolition of waiting shelter and goods shed has served to detract from the effectiveness of Culham as a Brunellian survivor, for these buildings were also original and in matching style. As the Great Western system spread, so the design was adapted to suit local conditions and materials. The Culham design, for instance, re-appears in stone and with detail alterations at Brimscombe, a once important point on the Gloucester line. The same pattern of detailing was used at Melksham and Bradford-on-Avon where the buildings were larger, and built of local stone. The second familiar Brunel type was entirely different and followed the Italian Classical style, becoming popularly known as the 'chalet' type. Brunel tried to make them merger into their surroundings: take away the awnings and you have a lodge house at the gates of a gentleman's park. Shrivenham station soon after its opening in 1841. A print by an unknown artist. This style of building, personally designed by Brunei, can be termed typical. It is recognisably 'Brunelian' yet it also has a unique quality of its own. This was the art of Brunei. He drew up four or five basic designs and then, by varying the building material, or an awning, produced a building that was at once both standard and unique. He was able to create the impression that the line from Paddington to Bristol was furnished with 'one off buildings without incurring the expense of such a policy. In drawing up his designs Brunel had to contend with two masters, the London and Bristol Committees under whose jurisdiction the line was divided. These bodies had differing opinions as to the amount of money it was permissible to spend on fine stations and embellishments generally, the Bristol men being more generous than their London based colleagues. This, in part explains why the stations at the eastern end of the line were so lacking in style. There were

other reasons: the country traversed by the Bristol section was hilly and therefore lent itself to fine cuttings, bridges \and tunnels, there were a great number of wealthy land-\ owners in the area which gave further incentive to elegant \ design and construction, and last but not least, there was a Plentiful supply of best quality building stone with which to construct the stations and tunnel portals and to form the elegant cornices, balusters and other embellishments with which Brunei decorated his work.Brunel was an artist as well as an engineer and varied basic design slightly so that the succession of stations along the line did not appear monotonously the same. He used diamond shaped chimneys as shown in type 'A', or a stack carrying stone slabs as in type 'C'. The former is usually associated with type 'A' but the diamond shaped chimney could be used on any of the styles. Brunei built his chimneys in limestone but sulphur and rainwater corroded the stone and the Company had to rebuild most of the old chimneys in brick. Windows and doors could be 'square headed' or have slightly pointed arches, though in the case of type 'C',

Brunel would not have produced all the drawings necessary to build the line, for each bridge needed half a dozen plans, but he made sketches, sometimes in pencil, of every item on the line with the dimensions he required and handed these to one of a number of draughtsmen who would eventually produce a set of water-colour tinted drawings to be used at the site of construction. Besides these working drawings there had also to be made contract drawings which were included with each legal document drawn up detailing the agreement between the Company and the contractor carrying out the work. There were also Parliamentary plans to be made for the information of the various committees of the House which were investigating the claims of rival concerns to the Great Western, or perhaps a lawsuit. The outline of the figure, a tunnel portal or a bridge or station was drawn to scale complete with measurements, in Indian ink on cartridge paper, and was then shaded with colour wash in various tints to show light and shade thereby giving a three dimensional appearance to the plan; each nut, bolt and rivet had its highlight and shadow to give 'roundness' to what would otherwise have been a flat octagon or circle on the paper. His early plans were made very handsome, almost works of art, by this technique. Brunel was a clever worker in water-colours as his 'artist's impression' of his proposed suspension bridge over the Avon at Clifton shows, (see L.T.C. Rolt 'Isambard Kingdom Brunel'), he was also a very quick and dextrous worker to produce so many fine plans so perfectly. When the drawings-or paintings-were complete Brunel passed them for use by marking them with his elegant, rapidly done, signature.

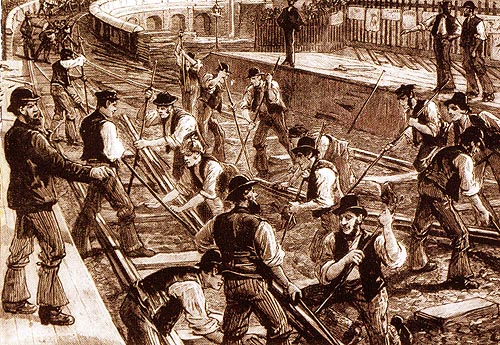

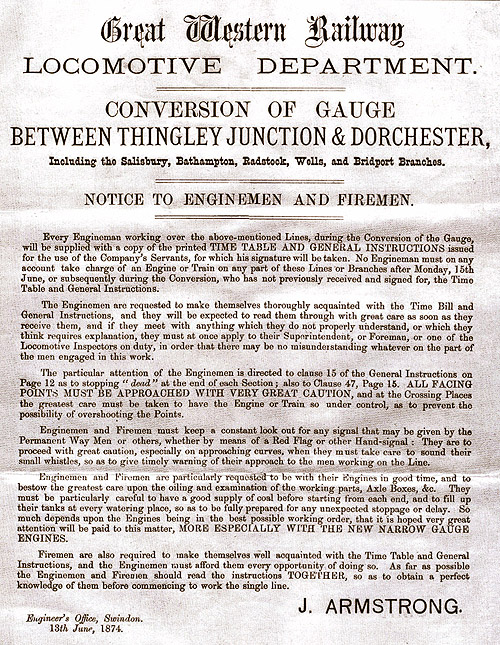

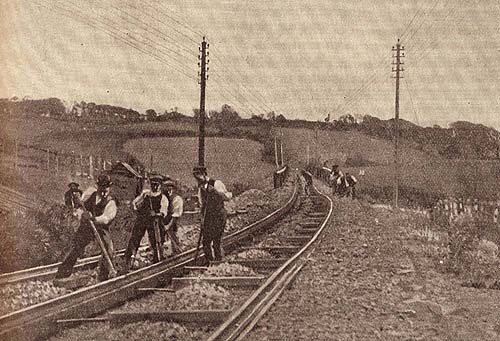

On 18 June, each

station-master was required to sign a certificate that his station and

district was clear of broad gauge rolling stock, the last trains arriving

at Chippenham about midnight. Much of the stock was later broken up at

Swindon, though the locomotives were sold for conversion to stationary

boilers. On 21 June standard gauge rolling stock was brought on to the

WSWR, 9 long trains of empty carriages coming from Swindon. Train services

re-commenced on 22 June-the whole task of narrowing 110 route miles (about

30 miles of this being double).

1877 The Signal Boxes installed at Bradford on Avon with 30 levers

and Bradford Crossing ( later known as Greenland mill Crossing)

1878 The timber viaduct east of Bradford-on-Avon station is rebuilt.

1885 With the opening of the Severn Tunnel, coal traffic developed

between South Wales and Southampton, and to facilitate working the single

line between Bathampton and Bradford was doubled throughout and new platforms

built at Freshford and Limpley Stoke stations.

1886 the Severn Tunnel opened . This famous tunnel, which reduced

the journey between Cardiff and London by one hour, cost almost £2,

000, 000.

1887 Seven trains ran from Bath- Weymouth plus three from Bath-Trowbridge

1895 a West Curve was laid at Bradford Junction to enable Bristol

Expresses to avoid Box Tunnel when covered in thick frost and still run

without reversal, Swindon - Chippenham - Bath.

January name changed to Bradford-on- Avon from just Bradford.

1906 Platform at Avoncliff opened

1914 When the Great War broke out, the Government, by an Order

in Council, assumed supreme control of all the railways in the United

Kingdom immediately after the declaration. When the war was finished,

the railways, the lines, the rolling-stock and plant which had been requisitioned

by the Government were handed back to their owners, and a measure of compensation

presented for the loss they had inevitably sustained.

1921 A Railways Act was passed which grouped all the numerous lines

and small independent companies into four big groups All the famous old

titles such as the "Great Northern" and "Caledonian"

vanished-all, that is, except the Great Western. The effect of the grouping

of the Great Western's mileage was to increase it by 560 geographical

miles, and by 3, 365 miles of single track.

1939-45 During the Second World War, Thingley Junction was also

made triangular with a West Curve again in 1943, to give more flexibility

in moving trains. Both these additional curves have now been removed in

modern times.

1948 Nationalisation of Great Western Railway. Under the Transport

Act 1947 the railways, long-distance road haulage and various other types

of transport were acquired by the state and handed over to a British Transport

Commission for operation. The commission was responsible to the Ministry

of Transport for general transport policy, which it exercised principally

through financial control of a number of executives set up to manage specified

sections of the industry under schemes of delegation. After the war the

"Big Four" railway companies of the grouping era were effectively

bankrupt, and the Act was intended to bring about some stability in transport

policy. As part of that policy British Railways was set up to run the

railways. Despite nationalisation and the creation British Railways (BR),

the rail system changed little, and was left in much the same way as it

had been before nationalisation. BR was divided into five administrative

regions, which closely mirrored the regions covered by the former companies

in England and Wales, although with the addition of a separate Scottish

Region. At first there was a separate North Eastern Region, although this

was eventually amalgamated with the Eastern Region, reflecting the English

operations of the LNER.

The Western Region built a large number of steam locomotives to GWR designs,

even after the advent of diesel shunters. The BR standard class 3 was

also built for the Western Region.

The Region experimented with diesel hydraulic traction such as the British

Rail Class 52 Westerns and British Rail Class 35 Hymeks based on West

German designs; these were all eventually replaced with British Rail national

standard diesel electric classes.

1961 The first regular diesel locomotive workings occurred on 16th

September, with a "Hymek" diesel hydraulic.

1964 2nd November becomes a Coal depot only. The goods shed lines

were reduced to one track, and the two sidings at the rear (and nearest

to) the shed became redundant.

1965 1 November. Closed to public goods traffic. When floods occurred

at Bradford the two road bridges became impassable and pedestrians from

one side of the town to the othere were allowed to walk along the rrailway

opposite Barton Bridge and the goods yard under the supervisioon of a

watchman .

1966 After the withdrawal of goods traffic the third siding at

the rear, together with the other shed road became disused in February

1966, and 5 months later, the same fate befell the up refuge siding and

both the main line trailing crossovers. At the same

time the signal box was closed. The

Greenland Mill Level crossing was fitted with automatic barriers in November

1966. Limpley

Stoke Station closed on 3 October.

1967 Station Masters House demolished. It stood at the corner of

Frome Road and Station Yard, where Fish and Chip Restaurant is now. The

last steam workings on the line.

1974 Health Centre built in Goods Yard in 1974/5

1976 One of the major triumphs of the Western Region was introduction

on the Great Western main line of the Intercity 125 trains in bringing

major accelerations to the timetables.

1984 In April of this year plans were announced to single the line

between Bathampton Junction and Bradford Junction, to be undertaken in

early 1986, in connection with saving renewal of much of the worn out

jointed track on the route. Following a Public outcry and a rethink by

British Railway , the plan was dropped in late 1984. ''British Rail planned

to single this stretch of line again in 1982 But the towns people thinking

it a false economy objected and two" thousand signed" a petition

against the idea_ which" was' never carried put

1988 In May of this year Sprinters displaced day to day Locomotive

hauled Passenger Trains on Portsmouth - Cardiff Route.

1991 In March Class 158`s-"Express Sprinter" arrive in

limited numbers.

1992 In In August, 1992, the double tricks on a normal weekday

carried 38 trains which stop at Bradford and 27 which rush through as

expresses.

1998 Railings between Station Forecourt and Goods Yard removed.

Station Refurbished by Rail Track.